Pierre Bonnard (1867-1947)

By Annabel van Grenen

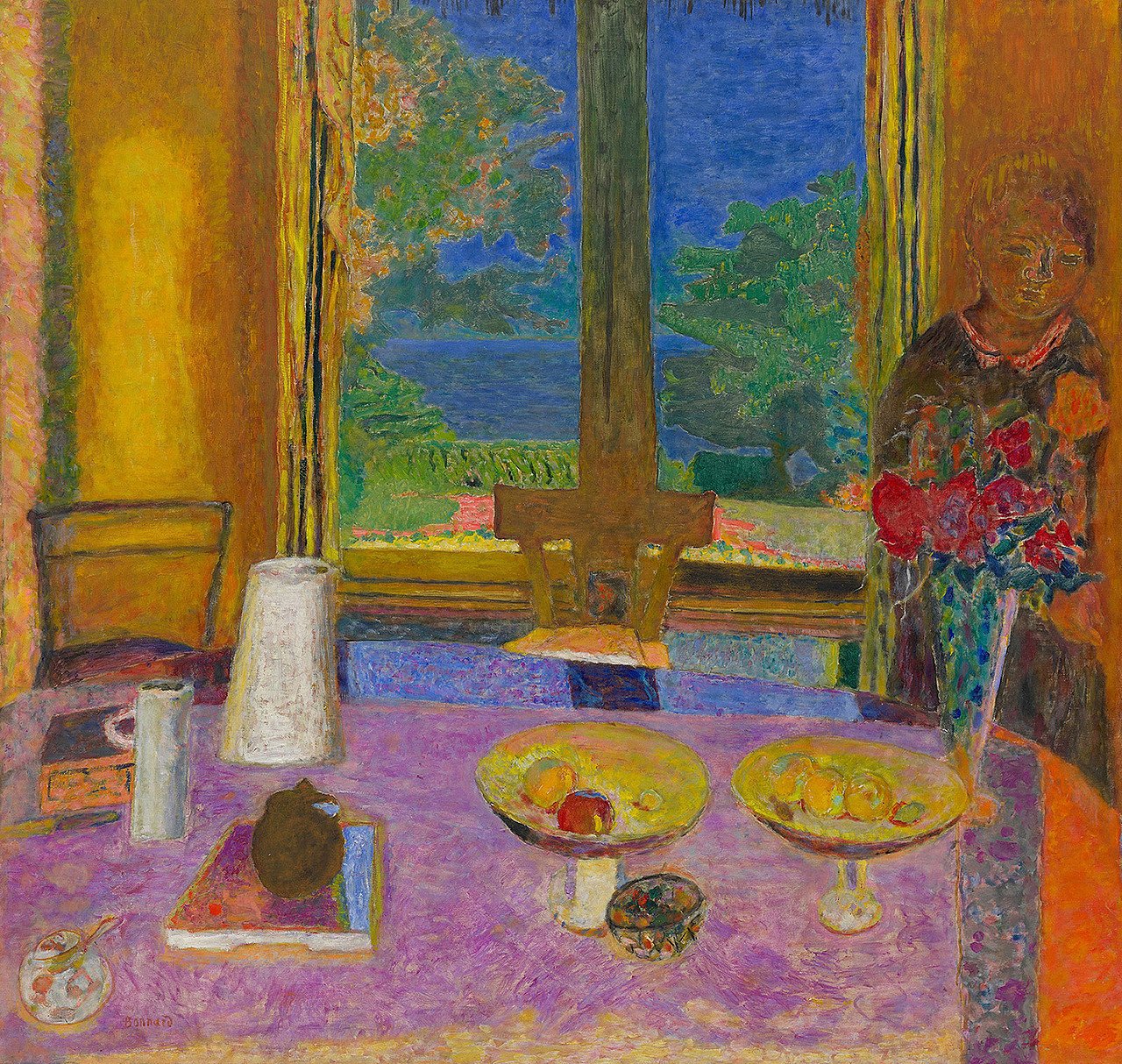

Pierre Bonnard, Dining Room on the Garden, 1934-35, oil on canvas, 127 x 135.3cm, Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum, New York.

Image courtesy of Solomon R. Guggenheim Museum.

Pierre Bonnard, born 3 October 1867, was a French lawyer turned intimist painter known for his domestic interiors, female nudes, and spirited use of colour. Whilst studying law, Bonnard was a student at the Académie Julian where he formed part of the avant-garde group Les Nabis and later attended the École des Beaux-Arts. The group facilitated the metamorphosis of Impressionism to Modernism, though Bonnard developed his own style before the dissolution of Les Nabis in 1900.

Until late, Bonnard was not nearly as renowned as some of his modernist peers of the nineteenth and twentieth centuries, such as Matisse and Picasso, having faded to the art historical outskirts. A recent revival of interest saw a Tate Modern solo exhibition in 2019, albeit to mixed reviews. One critic, Adrian Searle, complained that some of Bonnard’s paintings were “scrappy” and begged the question: ‘Why do people love him so much?’ I believe the answer lies in the forged intimacy of his paintings. For example, his painting Dining Room on the Garden (1934-35), pictured above, depicts an ordinary domestic scene with exceptionally vibrant colours, absent of the naturalistic palette that dominated the nineteenth century; the viewer is stuck in the realm between the familiar and the foreign. Rebecca Chamberlain and Robert Pepperell, art historians, noted Bonnard’s expert use of complimentary and equiluminant colours, used to blur outlines, is evident across the yellow and orange walls, purple tablecloth, and blue sea, drawing the viewer into a polychromatic fiction. The intimacy is curated by Bonnard’s rejection of linear perspective, rather painting objects as they are remembered, inviting the viewer to share his own memories used to produce the works. He also thrusts the viewer into a truncated picture plane, leaving them in an uncomfortable liminal space. The viewer is not alone, either, as his artworks often show a figure casually cut off by a window, a door, or the frame itself. Here, a woman leans against the wall and blends in, a ghost within the painting.

Bonnard married Marthe de Meligny, his wife and lifelong muse, in 1925. De Meligny was often the ghostly figure in his paintings, typically laid in a bath. This repetitive setting and pose produced an image of feminine passivity and morbidity, emphasised by its visual mirroring of John Everett Millais’ Ophelia (1851-52). So, whilst some artworks expressed the joy and simplicity of everyday life through brilliant structures of colour, other intimate scenes revealed an uncomfortable display of gender imbalance. Bonnard passed away in 1947, a year before a career retrospective at the Museum of Modern Art in New York City, originally intended as a celebration of his eightieth birthday.

Bibliography

Chamberlain, R., and Pepperell, R. “Slow Looking at Slow Art: The Work of Pierre Bonnard.” Leonardo 54, no.6 (2021): 615–618. https://doi.org/10.1162/leon_a_02054

de Bolla, P. “Pierre Bonnard: Bringing Painting to Life.” Boundary 2 49, no.2 (2022): 243–270. https://doi.org/10.1215/01903659-9644583

“Eight Essentials to Know About Pierre Bonnard.” Tate. https://www.tate.org.uk/art/artists/pierre-bonnard-781/eight-essentials-know-about-pierre-bonnard

Searle, Adrian. “Pierre Bonnard review: monumental, monstrous - and rubbish at dogs.” The Guardian. January 21st, 2019. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2019/jan/21/pierre-bonnard-the-colour-of-memory-review-tate modern-london

Wallace, L. “Who killed Marthe Bonnard? Madness, morbidity and Pierre Bonnard’s The Bath.” Journal of Contemporary Painting 4, no.2 (2018): 267–283. https://doi.org/10.1386/jcp.4.2.267_1