Czech Symbolism and Jan Preisler’s "The Lady on the Lake" (Žena u Jezera), 1905

By Lucia Hawkes

“Art has to come from within, from your innermost convictions, from the depths of your soul and feeling”

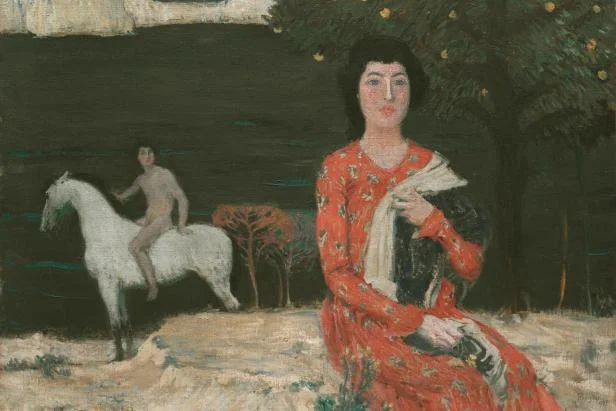

The artist Jan Preisler (b. 1872 – d. 1918) was born in Králův Dvůr, in the Czech Republic. He studied at the School of Applied Arts in Prague 1887-95, before becoming a professor at the Academy of Fine Arts, Prague, in 1903. Completed during his professorship at the Academy, Preisler’s The Lady on the Lake (1905) presents a captivating engagement with the themes of life and death, man and woman, darkness and light; a work which is conflicted, ambivalent and psychologically provocative. Drawing upon the deeply personal imagery of Edvard Munch and the nostalgic epic poems of Julius Zeyer – whose prose glorified an ancient Czech past – Preisler’s work is at once melancholic, decorative and nationalistic. In reaction to the vast urbanisation that had occurred throughout the nineteenth-century, Preisler and other Symbolist artists turned to the pastoral as a source of spiritual rejuvenation – to describe the primal and ‘innermost’ feelings of human nature. The foreground tree, mountainous backdrop, chalky terrain and sprouting flowers within Preisler’s painting evoke a sense of the rural and a rustic simplicity. Furthermore, Preisler’s impasto technique captures the rough texture of the rocky soil, also leaving areas of canvas visible to produce a raw, scratchy effect. As a result, the image exudes an almost crude naiveté, with flat stylised figures and roughly outlined forms.

Jan Preisler, Žena u Jezera, oil on canvas, (1905) 74 cm (29.1 in). Width: 100 cm (39.4 in), National Gallery in Prague.

https://theartstack.com/artist/jan-preisler/zena-u-jezera-1905

A depth of ‘feeling’ is embodied in the dark lake, a motif used repeatedly throughout Preisler’s oeuvre. In the visual language of Symbolism, water alluded to the state of unconsciousness, thus alluding to the deeply troubling, dubious and irretrievable parts of the human psyche – oblivion and the unthinkable. With its mirrored surface, water also indicates a self-reflexivity, often referring to the inwardness and vanity associated with the Narcissus myth. Additionally, using darker tones and a ‘shocking’ black, Preisler sought to enhance the sinister and brooding atmosphere of his lake scenes. While this darkness makes reference to death and stillness, Preisler’s lake is enlivened with a rippling surface which functions, conceivably, as a metaphor for the instinctual drives hidden beneath the human exterior. Likewise, associated with water in Greek mythology, the white horse represented intuition and instinct. To envisage a white horse in a dream was perceived as an omen of death – a warning of life’s transience and fragility.

During the Renaissance, the ‘horse’ became affiliated with sexual potency and was transformed into an emblem of insatiable desire, impulsiveness and animalistic lust. Straddled by a naked rider, Preisler’s white horse portrays a virility and masculine sexual power. Although the symbol of Preisler’s horseman is ambiguous, he could signify an externalisation of the female figure’s awakening sexual desire and internalised longings; a fantastical projection of female passion. This interpretation is supported by Preisler’s hazily rendered setting, which possesses a strange and imaginary quality. Significantly, the theme of masculine valour was prominent in Czech legend, whereby the equestrian emblem denoted National strength, encapsulated in Prague’s famous commemorative sculpture of Saint Wenceslas. The chivalric Knight thus pertained to war, nobility and honour – a boldness found in the strong physique of Preisler’s proud horseman.

Used frequently as a motif, the image of man and woman in a landscape, according to Petr Wittlich, proposed an allegorical representation of ‘the Czech democratic idea of the equality of the sexes’. Preisler’s inclusion of both man and woman in a georgic landscape also aligns the scene with the Garden of Eden. Situating his female figure in close proximity to a fruit-bearing tree, for example, Preisler associates womanhood symbolically with fecundity and Eve-like temptation. Moreover, Preisler’s figures appear androgynous – with both his masculine and feminine facial types exhibiting a profound resemblance. Preisler’s male figures were also often depicted with a boyish effeminacy, teetering on the boundary between adolescent virtuosity and sexual revolution. This liminal, sexless state alluded to unity, harmony and a heightened spirituality – expressing, perhaps, the Czech ‘democratic idea’ of gender ‘equality’ Wittlich refers to.

In contrast to this conception of genderless unity, through the use of empty space and compositional oscillation between closeness and distance, Preisler generates a discord between the figures. The voyeuristic gaze of the horseman, for example, produces a feeling of foreboding menace. It is also unclear as to whether the man’s presence is known to the woman; if she is conscious of his existence, then her positioning is defensive – yet if he signifies an extension of her internal desires, she appears in a trance-like stupor. Her blank, doll-like visage is reminiscent of and makes a stylistic reference to both the Slavic Babushka doll, and the portraiture of Japanese prints – with their characteristic bold, flat lines. In addition, Preisler’s facial rendering is also comparable to the manner of Ancient Greco-Roman funerary portraits, bearing the same discerning frontal expression and dark colouring – a style possibly witnessed during his wanderings in Italy. As a result, Preisler’s varied ancient and folk references serve to enhance the sanctimonious and furtive qualities of his figures, and, significantly, the obscure environment in which they reside.

Preisler’s image is at once poetic and ominous, portraying a scene of youthful desire and courtship. Through symbolic use of the horse and lake motif, Preisler examines themes of death and eroticism, the unknown and unknowable, instinct, nature, dream and nightmare. Preisler and other Symbolist artists also sought refuge in the natural landscape; a subject matter which provided a sense of hope, renewal and regeneration. Employing a colour scheme of predominantly black and white, alongside muted, earthy tones, Preisler projects an artistic scheme based upon the alternation between contrasting colours and concepts. Preisler’s use of dark tones reinforces the all-absorbing interiority associated with the lake motif, whilst his unsettling spatial recession contributes to and sustains the dream-like quality of the indeterminate setting. Fundamentally, Preisler’s image relies upon a system of interweaving symbols – the religious, ancient and erotic – to confound and construct its meaning. This internal tension thus pervades the painting with a sense of alluring unresolvedness; a mystery and intrigue that simultaneously troubles and enchants.

Bibliography

Cirlot, J. C., Dictionary of Symbols, (London: Routledge, 2006)

Howard, Jeremy, Art Nouveau: International and National Styles in Europe, (Manchester: Manchester University Press, 1996)

Krén, Emil and Daniel Marx, ‘Jan Preisler’, Web Gallery of Art, http://www.wga.hu/bio_m/p/preisler/biograph.html [30/08/2017]

Preisler, Jan, ‘Extracts from Speech at the outset of his career as a professor at the school of the Academy of Fine Arts’ (1913) in: Petr Wittlich, Jan Preisler 1872-1918, (Prague: Municipal House, 2003)

Wittlich, Pettr, Jan Preisler 1872-1918, (Prague: Municipal House, 2003)

Wittlich, Pettr, Prague: Fin de Siecle, (Paris: Flammarion, 1992)