The Art of the Market

by Jesse Anderson

The art market is no new phenomenon. For centuries, societies have been making and selling art, whether for the ceiling of churches or for the ownership of medieval Persian Princes. Though recently, with cases such as Inigo Philbrick and the $450.3 million sale of Leonardo da Vinci’s Salvator Mundi, the art market has been a topic of heated debate. So, how did we get here? What were the catalysts to the formation the $1.7 trillion art market of today? Though the present art market finds its foundations in a long history of producing and selling art, it was the events of the late twentieth century which fueled the art market’s sky-bound trajectory.

As far as we know, the most recognisable free market for art was established in the Dutch republic of the seventeenth century. Art dealers, aided by the invention of printed catalogues which described artists, began to take over a market previously dominated by artist workshops. Art could be sold to collectors without the presence of the artist, cementing the role of the art dealer. The Renaissance had reignited an admiration for art of the past, feeding a culture of collection whereby wealthy individuals bought art to present in their homes, inviting people to come view their collection as a gallery.

All this to say that the art market has been present for a very long time. However, the advent of Pop Art, amongst other factors, would contribute to the transformation of a global industry which would survive multiple financial crises.

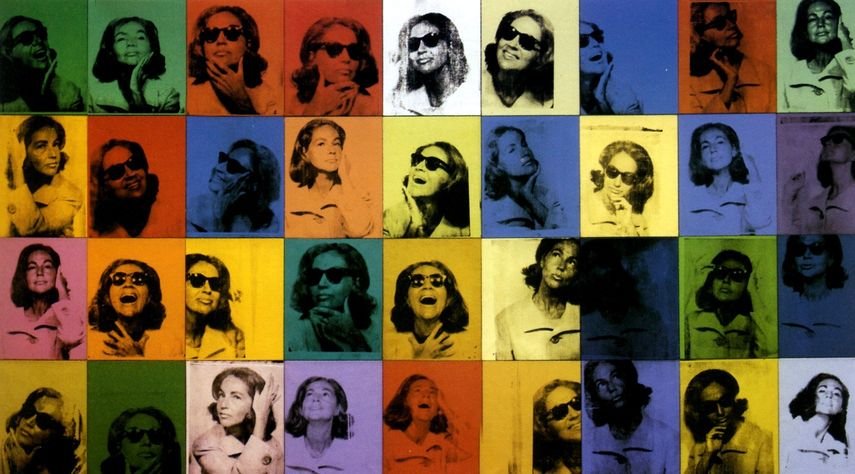

Andy Warhol - Ethel Scull 36 Times, 1963. Metropolitan Museum of Art and Andy Warhol Foundation for the Visual Arts / Artists Rights Society (ARS), New York

In the 1960s, Pop Art flourished both in the UK and America. It was a movement that rejected previous ideas of what art should be: what it should look like, what it should achieve. It was an art for the people, made up of symbols and images which surrounded the U.S population. In a disappointing paradox, while Pop Art explicitly regarded the commodified nature of art, it did not make gallery-hung art any more accessible to the everyday person in terms of ownership. Art became a lucrative business: Andy Warhol himself famously stated that “Being good in business is the most fascinating kind of art. Making money is art and working is art and good business is the best art.” Plainly stating the hard-drawn relationship between art and business. At the same time, big-time art dealers like Leo Castelli were representing artists as investments. Art became increasingly valuable not necessarily in terms of culture, but in terms of cash. Castelli helped artists like Warhol skyrocket to fame within their lifetime, an experience not known to the likes of Vincent van Gogh. Businessmen began to see art as an investment, something which could gain value over time. The inextricable link between art and capitalism was stronger than ever before.

Scull Auction, 1973

The 1970s consolidated the establishment of a modern, high-end art market. The new, or reinvigorated, understanding of art in relation to economics caused a huge expansion in the secondary art market. In 1971 ‘The Artists Contract’ was drawn up by lawyer Robert Projansky: this protected an artists’ rights to the ownership of their work amongst the growing secondary market. This decade also saw the monumental auction of the collection of Robert and Ethell Scull at Park Benet, now known as Sotheby’s. The couple, who had collected contemporary art throughout the 1960s, were auctioning off almost all of their collection. This particular auction is known as the ‘Scull Auction’ and is notable because it affirmed the high value placed on contemporary art. Art became an investment of interest to the government also: in the 1970s, the British Rail Pension Fund began investing in art and allocated £40 million to art investment. Clearly, art had gained a reputation as a valuable commodity, a dependable asset.

In the 1980s, amid the rise of yuppie culture, art prices drove even higher. Globalisation increased as communication technology advanced, and countries such as Japan came to play a sizeable role in the global art market. In 1987, Van Gogh’s Sunflowers saw an opening bid of $8 million at Christies, a sum to be quintupled in just five minutes. In 1987, the same year as the U.S. stock market crash, the Japanese fire company Yasuda bought the painting for nearly $40 million.

The almost surreal sensationalism growing in the art market was fueled by the ongoing financial appreciation for contemporary art. Suave excess was the theme of the art world in the 1990s, a world led by the Young British Artists. Damien Hirst, Tracey Emin, and Sarah Lucas are just a few of the individuals who headed this group. Charles Saatchi exhibited their work in his gallery in 1992, under the exhibition title Young British Artists. Ben Lewis in The Guardian writes that ‘The YBAs [Young British Artists] accelerated the trajectory of artistic style towards production line and brand identity’ demonstrating the continued theme of explicitly commodified art.

The 2000s were another rocky decade of financial highs and lows. The opening of the Tate Modern in 2000 encouraged, and confirmed, a global interest in contemporary art. Perhaps more important, public accessibility to the internet posed myriad possibilities for the direction of the art world. Websites like Christie’s and Sotheby’s could host online auctions, and Ebay provided an additional space for everyday people to sell and purchase art. The online market continued to grow throughout the 2010’s as auction houses held sales live online. Accessibility of information was essential for the establishment of online marketplaces, meaning that the art world became a little more accessible to anyone with access to the internet. Financial inaccessibility, however, stayed the same.

Sotheby’s Auction, May 2022

Now, in the age of hyper internet accessibility and data sharing, it’s hard to predict in which direction the art market will go. In terms of auctioning, Sotheby’s and Christie’s still reign as the largest auction houses, now dedicating auctions to art such as NFT’s. The morality of the art market in the current financial and social climate is still under dispute, especially following the tumultuous case of Inigo Philbrick. And just because the art market can now exist in online spaces does not mean it is accessible to the everyman: just three years ago, Banksy’s Love is in the Bin, was sold to a private collector for £18.2 million. But what industry is morally sound? Do we place higher expectations on the art market because we cannot dissociate art from commodity?

How do we navigate moralities of the art market in a capitalist society? It feels strange to watch private investors spend more on paintings than we might make in our entire lifetimes. In 1975, artist Ian Burn wrote an article in Artforum describing the artists’ experience of the art market, describing his alienation from his own work. ‘Not only do works of art end up as commodities, but there is now an overwhelming sense in which works of art start off as commodities.’ A depressing insight into how capitalism has permanently altered the role of art in the modern world. In his 2014 novel, Playing the Gallery, Grayson Perry talks briefly about the way in which the art market has given the public a means to understanding the value of art through figures. We may feel unsure of what makes an artwork ‘good’, but we do know that $450 million is a large sum of money. Conflicting discussions about the art market have long been chewed over by artists and art-lovers, yet the answer feels increasingly out of reach.

Inigo Philbrick’s lawyer infamously stated that the art market was corrupt, through and through. Whilst I do not wholeheartedly agree with this, I do have mixed feelings about the art market. It’s hard to find good qualities in an industry that commodifies human expression.

Bibliography:

Alberge, Dalya. 2022. 'He's sabotaged his entire life for greed': the $86m rise and fall of Inigo Philbrick. May 25. Accessed January 26, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2022/may/25/inigo-philbrick-jailed-art-fraud.

Andipa, Acoris. 2023. Andipa. July 25. Accessed January 26, 2024. https://andipagallery.com/blog/106-the-most-expensive-banksy-paintings-as-sold-at-auction/.

Burn, Ian. 1975. Artforum: The Art Market: Affluence and Degradation. Accessed January 26, 2024. https://www.artforum.com/features/the-art-market-affluence-and-degradation-212706/.

Hall, James. 1995. Artforum: Young British Artists VI. Accessed January 26, 2024. https://www.artforum.com/events/young-british-artists-vi-211966/.

Lewis, Ben. 2011. The Observer: Charles Saatchi: the man who reinvented art. July 10. Accessed January 26, 2024. https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2011/jul/10/charles-saatchi-british-art-yba.

Primary Information: The Artist's Reserved Rights Transfer and Sale Agreement. Accessed January 26, 2024. https://primaryinformation.org/product/siegelaub-the-artists-reserved-rights-transfer-and-sale-agreement/.

the warhol. Accessed 01 26, 2024. https://www.warhol.org/andy-warhols-life/#:~:text=As%20equally%20as%20he%20was,to%20finance%20his%20artistic%20ventures.