The Archive of Girlhood: Petra Collins on Reframing Fangirl

By Hanna Yoon

Petra Collins, Fangirl Portraits, 2025.

Image courtesy of the author.

When photographer Petra Collins calls her first major museum exhibition Fangirl, she’s daring us to take seriously what art history so often dismisses: the messy, glowing, sometimes obsessive spaces of girlhood and desire. Walking through the Daelim Museum in Seoul with Collins herself this summer, I felt the familiar thrill of being both inside someone else’s dream and reminded of my own. The rooms were saturated with violets and pinks, video projections pulsed with half-remembered pop songs, and walls bloomed with photographs of adolescent bedrooms, fashion spreads, and portraits. Engrossed by a fever dream curated with equal doses of tenderness and unease, it made me wonder: why has art history been so slow to take the teenage girl seriously as both subject and maker?

Cindy Sherman, Untitled Film Still #10, 1978. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Image courtesy of MoMA.

Georgia O’Keeffe, Close-up of Flower Abstraction, 1924. The Whitney Museum of American Art, New York. Image courtesy of the Whitney.

Collins’ work exists within a lineage of artists who turned the gaze inward, transforming identity and fantasy into high art. Cindy Sherman’s constructed personas in her Untitled Film Stills feels like an older cousin to Collins’ self-portraits, which fluctuate between performance and sincerity. Yet where Sherman’s women often inhabit clichés of femininity—housewife, femme fatale, ingénue—Collins offers something stranger and more fragile: the girl who isn’t quite finished, who is half-online, half-asleep, and half-becoming. Collins has also cited renowned modernist painter Georgia O’Keeffe as an influence. O’Keeffe’s Flower Abstractions were once read scandalously as female bodies—Collins notes, ‘O’Keeffe had a lot of things imposed onto her; while she was trying to create her own world people would always take her world out of it.’ In the same sense, Collins places the intimate and the bodily at the center of her images, however battles between the hypersexualized impressions of her work and staying true to her ‘world.’

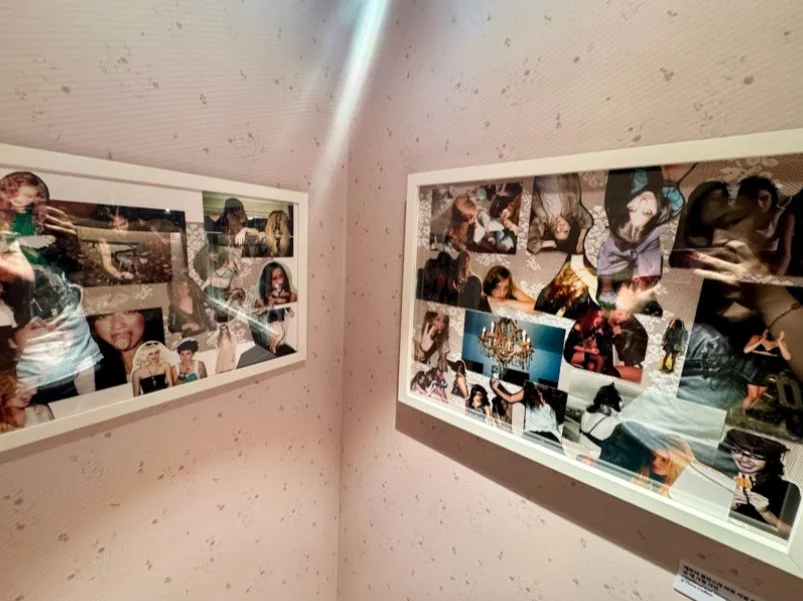

Petra Collins, Fangirl Moodboard, 2025.

Image courtesy of the author.

Art history often valorizes the grand and monumental, but Fangirl insists on the small: the scrapbook, the magazine tear, the selfie or ugly yearbook photo. Wandering through the archival sections of the exhibition, where Collins displayed mood boards and editorial clippings, I realized she was treating fangirl culture as both subject and methodology. In a way, she is creating what German cultural critic Walter Benjamin once called the ‘arcades of modernity,’ except hers are plastered not with Parisian shop windows but with the Tumblr-esque ephemera of early internet and teen devotion. If Benjamin sought to rescue the overlooked fragments of modern life, Collins is doing the same for girlhood—archiving its debris before it vanishes in the ever-growing digital wasteland.

Petra Collins, Anna & I, 2025.

Image courtesy of the author.

And yet, beneath all the sweetness and dreamy haze, there is something unsettling. Collins’ work refuses to let us rest in nostalgia. Just when you begin to savor the soft lighting and pastel hues, she slips in distortion, masks, and uncanny doubles—it raises the question: how authentic is any self we construct in images? In the booming age of social media, Collins’ work feels like both a prophecy and a diagnosis. She reminds us that the image and the art is always mediated identity—consider the stiff Victorian portrait, the Renaissance profile, or the Cubist expressionism. But in the twenty-first century, this process is hyper-accelerated, more intimate and infinitely more public.

Perhaps this is why Fangirl is so profound: it repositions the supposedly playful. The word ‘fangirl’ has long been used dismissively, a shorthand for female excess and irrational attachment. But Collins flips it into a serious aesthetic and artistic category, suggesting that longing, devotion, and mimicry are forms of creativity themselves. If we take art history seriously as the study of how humans shape meaning through images, then what could be more worthy of study than the ways girls have constructed selves, desire, and entire visual cultures out of scraps, songs, and screenshots?

Leaving the exhibition, I thought of Virginia Woolf who said, ‘nothing has really happened until it has been described.’ Petra Collins is describing girlhood in images and art, giving form to something often ignored or dismissed. But she’s also doing more: she’s modifying the narrative itself, blurring the boundaries between the commercial and the personal, the authentic and the performed, the dream and the archive. Fangirl is both an homage to the lives lived in bedrooms and screens, and a reminder that the history of art must stretch to include them.

And maybe that’s the most radical part of Collins’ project. She makes us realize that to fangirl is to archive, to construct, and to create. To fangirl is, in its own beautiful way, to make art history.

Bibliography

“Cindy Sherman. Untitled Film Still #10. 1978 | MoMA.” n.d. The Museum of Modern Art. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/56555.

May-Hobbs, Moses. 2022. “Walter Benjamin’s Arcades Project: What Is Commodity Fetishism?” TheCollector. November 8, 2022. https://www.thecollector.com/walter-benjamin-arcades-project/.

“Petra Collins on the Enduring Impact of Georgia O’Keeffe – HERO.” 2016. Hero. 2016. https://hero-magazine.com/article/70037/petra-collins-on-the-enduring-impact-of-georgia-okeeffe

Whitney Museum of American Art. n.d. “Georgia O’Keeffe | Flower Abstraction.” Whitney.org. https://whitney.org/collection/works/984.