Review: Albukhary Gallery of the Islamic World

By Nisan İğdem

The Albukhary Foundation Gallery of the Islamic World at the British Museum, 2018 © Trustees of the British Museum.

https://www.theartnewspaper.com/review/british-museum-s-islamic-art-finally-gets-its-fairy-tale-ending

On 18 October 2018, the British Museum opened its new gallery dedicated to the Islamic world. Sponsored by the Malaysian Albukhary Foundation, which focuses on education and cultural heritage, the gallery is placed in two Victorian halls (Room 42 and 43) restored by the foundation, and focuses on Islamic art from the seventh century to modern day.

The gallery space is divided into little booths that are dedicated to specific places, and more or less provides a chronological order of the exhibited material. The first room takes the visitor up to the beginning of the 14th century, while the second room reaches the art of today. The material goes from ceramic-ware, to tiles, fabrics and modern art. The Islamic world’s relationship with the West is also introduced with displays on Spain or Byzantium. The writings on the displays are written in Arabic script, as well as in English, which gives them a different texture, though it is important to bear in mind that not all of the Islamic world speak Arabic or use Arabic script.

In Islamic belief, the figural representations of humans and animals are forbidden, since it would be seen as imitating God. However, the visitors expecting to never see a human figure would be disappointed. As Hamzanama (The Book of Hamza) produced in India in 1564-1579 shows, there are figural representations in Islamic art. Still, the artists avoided using shaded compositions or perspective in the manner of the West, and preferred flatter images, possibly to not come too close to realism.

The Hamzanama, Elias and Prince Nur ad-Dahr, ink and opaque watercolour on cloth. Mughal style, India, 1564–1579.

https://blog.britishmuseum.org/a-journey-through-the-islamic-world-in-eight-objects/?_ga=2.57084393.2106655954.1556016349-1003548003.1556016349

One of the exciting materials in the gallery is an astrolabe from 1240s Turkey, Iraq or Syria. An astrolabe was used for a various of reasons, ranging from locating the stars to finding the direction of Mecca. However, the astrolabe exhibited in the British Museum is more likely for presentation rather than function. It still bears the name of the ‘astrolabist,’ as well as its patrons, thus documenting the status of science and patronage of its time.

Astrolabe, made of brass inlaid with silver and copper. Probably southeast Turkey, northern Iraq or Syria, AD 1240/1.

https://blog.britishmuseum.org/a-journey-through-the-islamic-world-in-eight-objects/?_ga=2.57084393.2106655954.1556016349-1003548003.1556016349

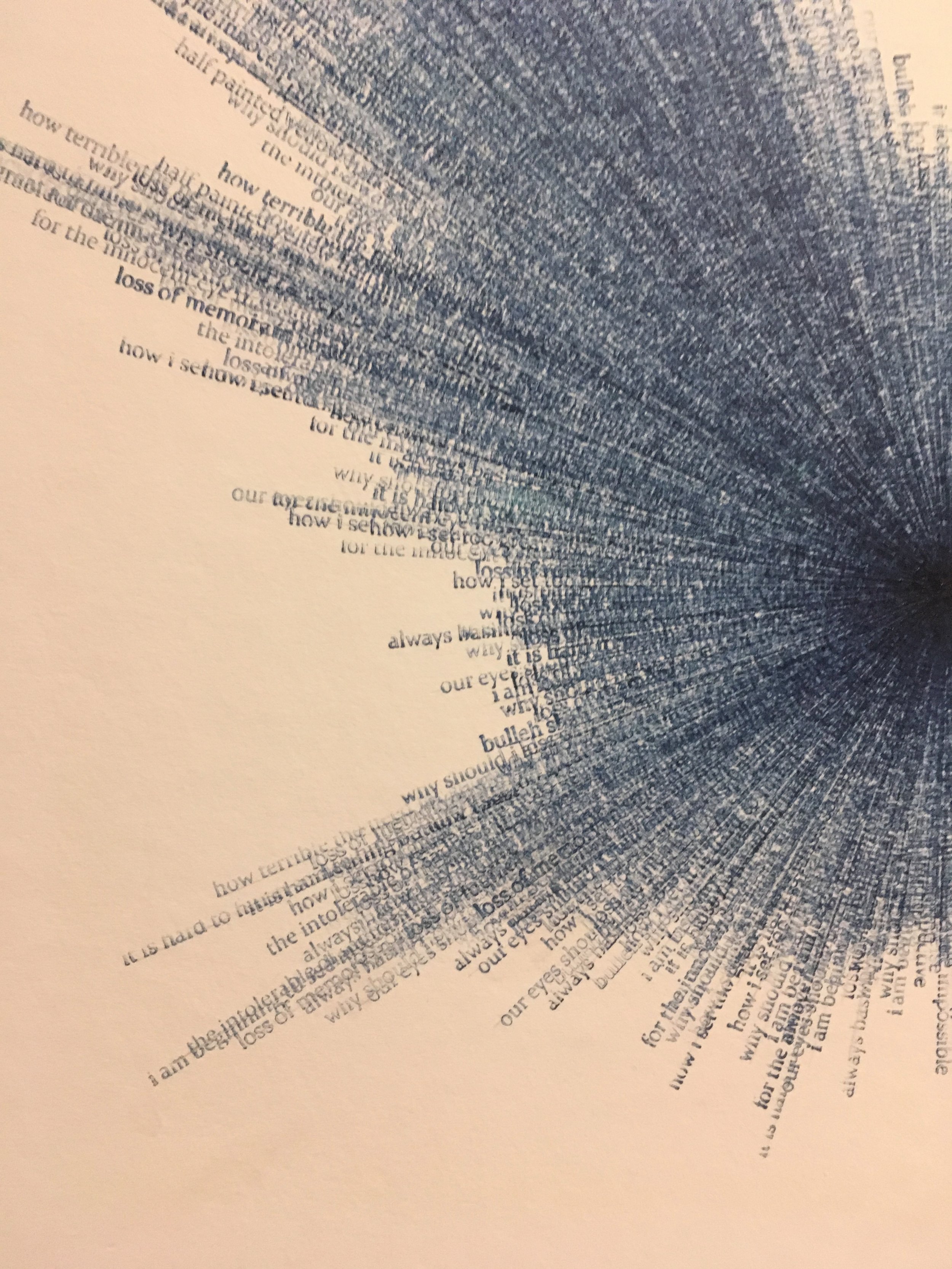

Another interesting work of art in the gallery is 21 Stones. The work, commissioned specifically to be exhibited in this gallery, consists of 21 paintings on a white wall. It alludes to the stoning of the devil ritual that takes place during the Hajj pilgrimage, in which the pilgrims collect pebbles and throw them at the three pillars. The artist Idris Khan explains his artwork as, “[the explosion of the] words and the prayers that the stone represents into a physical language”. The stamped words on canvas are instances from the artist’s life.

Even though the British Museum has been a little late to include an Islamic world section in one of the largest history museums, the Albukhary Gallery of the Islamic World is a great point to start including the East into the world history. The gallery is, of course, free of charge, and is worth a visit - or maybe, two.

Idris Khan, 21 Stones, 2018, British Museum. photo by Nisan İğdem.

Detail 21 Stones, 2018, British Museum. photo by Nisan İğdem.

Bibliography

British Museum, ‘A Journey Through the Islamic World in Eight Objects’ in British Museum Blog, 18 October 2018. (https://blog.britishmuseum.org/a-journey-through-the-islamic-world-in-eight-objects/?_ga=2.57084393.2106655954.1556016349-1003548003.1556016349)

Jake Jakeman, ‘British Museum’s Islamic Art Finally Gets its Fairy-Tale Ending’ in The Art Newspaper, 2 November 2018. (https://www.theartnewspaper.com/review/british-museum-s-islamic-art-finally-gets-its-fairy-tale-ending)

Jonathan Jones, ‘'A Soaring Miracle of Art' – Albukhary Gallery of the Islamic World Review’ in The Guardian, 16 October 2018. (https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2018/oct/16/british-museum-albukhary-foundation-gallery-of-the-islamic-world-review)