Magic of the North: Edvard Munch at the Berlinische Galerie

By Anna Marweld

Perhaps most famous for his emotionally overwhelming and incisive piece The Scream, Norwegian-born Edvard Munch is an artist who never fails to capture any given spectrum of psychological states. Munch’s childhood was plagued by poor health and bereavement, and he turned to art as a means of catharsis. The exhibition ‘Magic of the North’ at the Berlinische Galerie features 80 of the Norwegian’s works, each one more beautiful, more bewitching, than the next. Munch’s use of bright, unsettling colours and his aptitude for creating haunting facial expressions both reflect the horrors in his past, but also firmly embed him in the Western canon of art.

Figure 1: Edvard Munch, Madonna, 1895-1902, lithograph and woodcut, 60.5 x 44.5 cm, Berlinische Galerie, Berlin. [Photo credit: Anna Marweld]

One of the first and perhaps most memorable works of the exhibition is Munch’s Madonna lithograph print (Fig. 1). Unsettlingly erotic and enticingly provocative, Munch makes a blasphemous reference to the Virgin Mary in this work. Munch’s experiences with women conflate here with the changing cultural climate of the late nineteenth century, where blossoming liberal attitudes to sexual freedom opened the floodgates to both pleasure and vulnerability. As a symbolist, Munch rejects the previous practices of studying the external world, and, in its stead, turns his art inward. Spermatozoic shapes dance along the garish orange frame, trapping the sensuous nude inside of her dark surround. She appears blissfully unaware, her ghostly pale beauty dissolving into the tenebrous gloom. Gazing up at her reproachingly is a foetus in the bottom left corner, shrinking away from the glowing woman. In this work, Munch’s complicated relationship to femininity becomes apparent. This devotional depiction both venerates and demonises. Madonna is ecstatic in her femme fatale power, her dark potency overpowering the male viewer. It is unclear whether she is lying down or rising before us, the ambivalence of her pose reinforcing the murky interconnections between Munch and his sentiments towards women. Madonna is a shrine to love, danger, and pleasure.

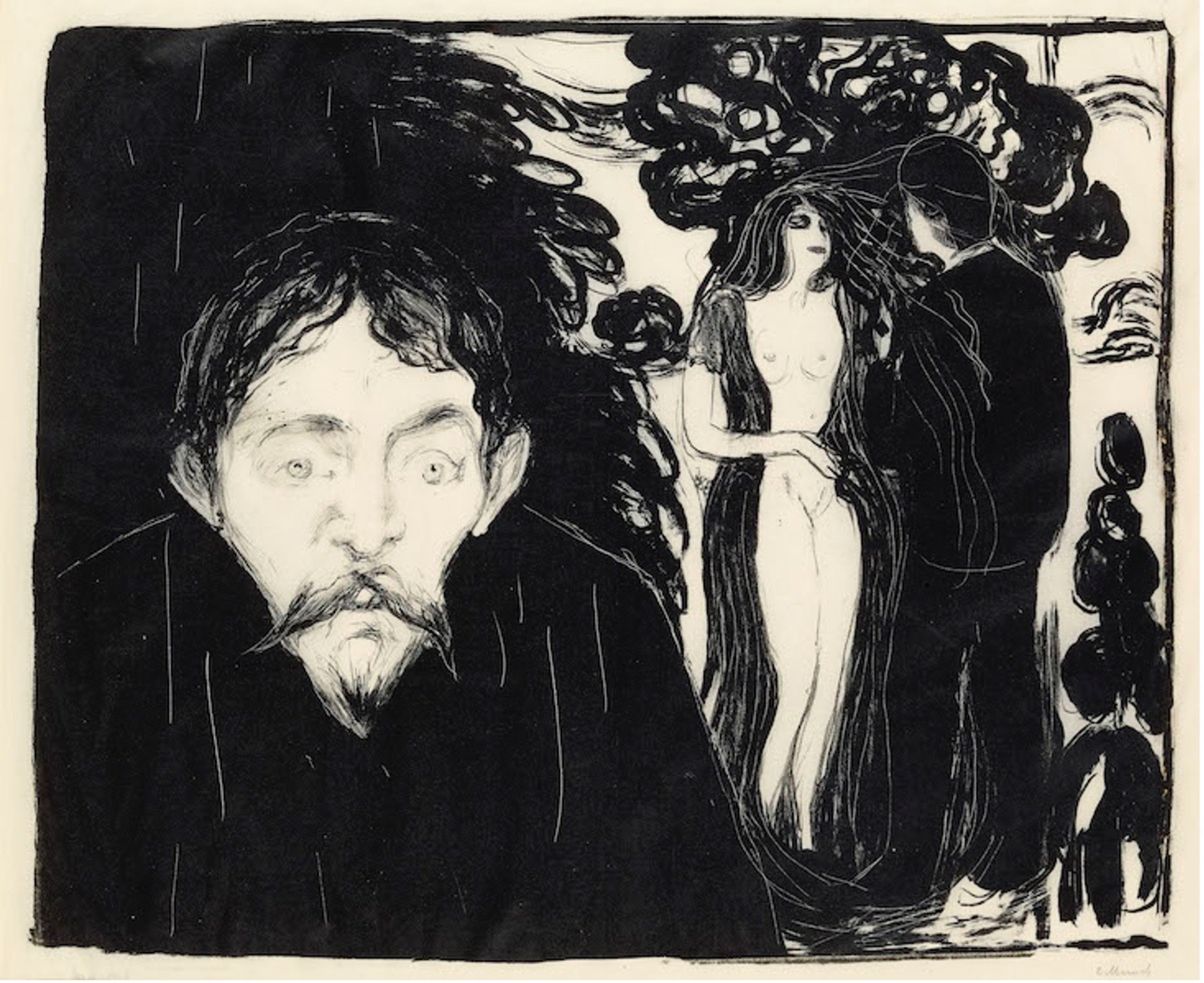

Figure 2: Edvard Munch, Jealousy II, 1896, lithograph, 61.2 x 75.3 cm, Museum of Modern Art, New York.

In Jealousy II (Fig. 2) Munch presents us with a classic state of psychological angst. Featuring Munch’s friend Stanislaw Przybyszewski in the foreground, Munch himself is rumored to be the figure in the back, engaging with Przybyszewski’s wife, Dagny Juell. Munch and Juell were presumed to be lovers. The love triangle, here, is depicted by Munch as a sinful temptation. Juell takes on the role of Eve, picking the apple in Eden and thus re-enacting the original sin. This quasi-biblical scene occurs behind the truly haunting figure of Munch’s friend. Driven mad by his jealousy – his wife and friend absorbed in flirtation – Przybyszewski’s eyes are wide and bottomless in their despair. He is shaken by the terrible reality he must face. Here, again, we see Munch’s skill in exploring humanity’s most treacherous psychological states, lending them a ghost-like and poignant quality. Munch’s own burdens manifest in his work, providing him the ability to depict torment like no other.

Figure 3: Edvard Munch, Red and White, 1899-1900, oil on canvas, 93 x 129 cm, Munch Museum, Oslo.

In Red and White (Fig. 3) we see another image of juxtaposing femininity. The two women before us are archetypes of womanhood – purity and passion, white and red respectively. The woman on the left, dressed in white, looks out pensively over the fjord. The woman in red looks at the viewer directly, confronting us. Behind them, the pine forest recedes into the depths of the pictorial space, the darkness and mystery of the woods clashing with the peace and light of the sandy fjord beach. Munch establishes two stages, or two characters, of femininity. However, it is the one representing lust and passion, perhaps even maturity, which faces us – innocence has turned, avoiding the encounter with the viewer. One can feel the eyes of the red woman even when walking away. Munch provides us with two sides of women – possessing both dangerous erotic power and innocent purity. Again, his conflicted views on the female sex rise to the surface of his works. Red and White draws the viewer into its enigmatic Scandinavian landscape and envelops us with a feeling of being watched, of being appraised.

Figure 4: Edvard Munch, The Sin (Woman with Red Hair and Green Eyes), 1902, lithograph, 69.5 x 40 cm, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

Troubled by a childhood torn apart by grief and madness, Munch’s life was marked with his own poor health and psychoneurosis. Subject to hallucinations and feelings of persecution, Munch suffered a string of personal tragedies. To say he was dealt an unfortunate hand would be a severe understatement. Nonetheless, Munch was able to transform blistering pain into vivid fantastical beauty. His often complex and vehement relationships with the women in his life are reflected in his work, which are tributes to the raw erotic power of women, tinged with dangerous anticipation and attraction. He follows the popular fin-de-siècle trope of the femme fatale, but also offers us views into the Scandinavian landscape. Branded as a ‘degenerate’ artist by the Nazis, Munch’s work now remains as a testament to his turbulent life, but also his raw talent and breath-taking sensitivity for colour and labyrinthine human emotion. His intricate yet fiery depictions of torment, lust and all other dimensions of human suffering and ecstasy made this an exhibition truly impossible to forget.

References

Edvard Munch. Madonna. 1895–1902 | MoMA. Accessed February 5, 2024. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/62017.

“Edvard Munch.” Berlinische Galerie. Accessed February 8, 2024. https://berlinischegalerie.de/en/exhibitions/preview/edvard-munch/.