Locating the Uncanny: Scotland’s Gothic Haunts

By Megan Waugh

With the recent release of Guillermo del Toro’s film adaptation of Frankenstein, the haunting character of Scottish scenery has once again been brought to the spotlight. Del Toro, known for films such as ‘Crimson Peak’ and ‘Pan’s Labyrinth’, shows a devout passion for the Gothic and fantastical. Through film creation, he has been ‘able to parlay his childhood love of the macabre into a highly successful career’; an ambition that has been met by his most recent project, as perhaps no story has been quite so influential for the Gothic as Mary Shelley’s novel Frankenstein. The tale warns against the limits of human agency and the divine, as its over-ambitious scientist attempts to ‘play God’ and create life from the dead. Rich in sustenance, its film adaptation required visuals which could match its wonder. When Del Toro began his writing process, he embarked on a scouting tour to locate potential filming sites and wells of inspiration. Although he travelled across much of Europe, no country bewitched him quite like Scotland.

Director Guillermo del Toro in Scotland.

Image courtesy of Ken Woroner, Netflix.

Tamara Deverell accompanied him on this trip, stating: ‘We were looking for neighbourhoods, rather than specific buildings, but we couldn't help finding inspiration in everything we saw.’ Deverell describes a charm that is ubiquitous; found manifest not just in notable Gothic exteriors, but of a more widespread, emanating quality. As a result, many of the elements included in the film are taken from a wide variety of locations: ‘The Gothic arches in the creature's cell are from the vaulted arches of the cloisters at the University of Glasgow. And the tiles are from a swimming pool, built in the 1800s, which we didn't even get to visit because it's on an island [Mount Stuart, on the isle of Bute] but the tiles still made it into the final film.’ Like Frankenstein himself, the production team pieced together pockets of inspiration to take on new kinds of life and representation in the film.

Excerpt from The Art & Making of Frankenstein.

Image courtesy of Netflix/Insight Editions.

In the introduction to the 1831 edition of Frankenstein, Shelley describes her ‘considerable time’ spent in Scotland, noting that though she made ‘occasional visits to the more picturesque parts’, her primary residence was ‘on the bleak and dreary northern shores of the Tay, near Dundee.’ She cites it as a place of creative flourish: ‘the eyry of freedom, and the pleasant region where unheeded I could commune with the creatures of my fancy.’ Further, that it was where ‘my true compositions, the airy flights of my imagination, were born and fostered.’ Scotland provided inspiration for Shelley’s imagination in such a way that was as unconventional as her own writing. Whilst many artists’ creativity is often attributed to extreme splendour and beauty, Shelley found sublimity and fulfilment in the ‘bleak’ and ‘dreary’. It presented a paradox: creation and flourishing at the site of sallowness and degradation – key themes of her novel.

Mary Shelley. Photograph by Annan & Swan.

Image courtesy of Florence A. Thomas Marshall.

Experience of contrast like this is common against many of the uncanny elements Scotland presents. Ian Duncan attests Scotland’s Gothic cultural identity is a result of its unique and obscure national identity. At the time of the genre’s flourishing, its ‘image’ was being created through a juxtaposition of both its natural and urban connotations. Whilst anxiety felt towards modernity led many to romanticise Scotland as a site of pre-modern sanctuary, it simultaneously harboured a reputation of rampant industrialisation. This, in tandem with its struggle to define itself against England’s shadow, put Scotland in a potent position of precarious identity. In 1936 Edwin Muir anointed Scotland’s lack of cultural identity with the fact that ‘Scots feel in one language and think in another’.

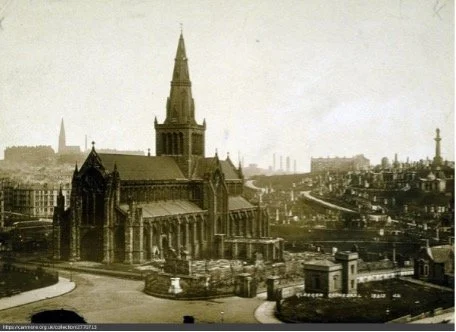

In spite of this, there are modes of articulation through which Scotland fails to be misunderstood. The over-reaching sublimity Deverell and Shelley describe stands as testament to a language which Scotland has mastered: that of hope and sublimity. One of the film’s locations, Glasgow Cathedral, is one of two Gothic cathedrals remaining in Scotland. Around 600 AD, St. Mungo built his chapel at this site, and when he died, the cathedral was erected over his grave. From here, the city of Glasgow gained life, sprouting out around it.

Glasgow Cathedral, 1893. Image courtesy of Records of the Scottish Cultural Resources Access Network (SCRAN).

When we see these Gothic structures today, their ornateness appears uncanny against the modern landscapes they protrude against. Their detail and artistry appears almost unfaithful to the modern simplicity more akin to our reality today. Nonetheless, they stand paramount, prevailing against the passage of time as monuments of great hope and divinity. Their co-existence with modernity shows an everlasting co-existence of grand and bleak, light and dark. That in these strange paradoxes, we may still find a shared unity: beauty.

Bibliography

Biography.com Editors. ‘Guillermo del Toro Biography.’ The Biography, September 21, 2015. https://www.biography.com/movies-tv/guillermo-del-toro

Cook, Daniel. ‘Mary Shelley and the Scottish Gothic Tradition.’ National Library of Scotland. https://www.nls.uk/collections/stories/literature-and-poetry/mary-shelley-and-the-scottish-gothic-tradition/.

Davis, L., Duncan, I., & Sorensen, J. Scotland and the Borders of Romanticism. Cambridge University Press, 2004.

Marshall, Florence A. Thomas. The Life and Letters of Mary Shelley. Richard Bentley and Sons, 1889.

McLean, Pauline. ‘How Scotland shaped Frankenstein on page and screen.’ BBC Scotland. October 30, 2025. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/articles/cm2l38my7m1o#:~:text=After%20hundreds%20of%20film%20adaptations,200%2Dyear%2Dold%20story.

Muir, Edwin. Scott and Scotland: The Predicament of the Scottish Writer. Polygon Books, 1932.

Shelley, Mary. Frankenstein. The Penguin English Library, Penguin Classics, 2012.