Art of Advent Day 15

By Anna Barlow

Archibald MacKinnon, Hogmanay at the cross, Campbeltown, 1899. Oil on canvas, 60.6 x 91.6 cm, Campbeltown Museum.

Image courtesy of Argyll and Bute Council and CHARTS.

As the festive season approaches, the shops of Scotland erupt with decorative displays, Christmas specials flood our screens, and cards fill our letterboxes from loved ones, printed with everything from nativity scenes to gingerbread folk. There is a complete visual takeover, whether it be commemorating the birth of Christ or the Viking winter solstice: Christmas is a celebration of creativity, but undoubtedly, commercial charm.

However, underneath the beauty of holly and mistletoe lies a much pricklier question: is Christmas suffocating authentic artistic creativity? After all, it is at this time of year when corporate companies churn out designs in an industrial assembly line. For some, it’s a field day, but for others, a festive pressure cooker to produce seasonal kitsch by the crate.

Before delving into the effects of capitalism on Christmas’s creative flair, we must recognize Scotland’s unique connection with the holiday. Made illegal by an act of Parliament in 1640, any act in celebration of Christmas, even something as simple as making a mince pie, was a criminal offence. Why? According to the Presbyterians, it was a hedonistic free-for-all, clashing with puritanical principles of restraint and anti-materialism at the heart of their dogma. Instead, Scots shifted their celebrations with greater emphasis to Hogmanay, a secular New Year’s tradition that was more palatable to the Church. Christmas didn’t become an official national holiday once more until 1958: over 300 years later.

In a twist of historical irony, the festival that was once banned for excess, has now made a full-blown resurgence as a capitalist extravaganza. Skyrocketing through Americanised advertising — a modern-day Claxton printing press — rapidly producing imagery that reinstated this beloved tradition in Scottish culture: Yuletide.

Christmas today is a holiday of money-making, but where there is interest in profit, there comes great pressure. The result in the eyes of the art snobs, is an influx of kitsch or ‘worse art’. Our jolly festive season has been coupled with a loss of creativity: a conveyor belt for card, cracker, and candy cane cliché’s rather than authentic expression.

I would not place myself in this category of person. Any claim that art is for a specific purpose or should look a certain way can always ultimately be unpicked. However, there is something to be said about the negative effects of Christmas on the artist.

There is historical precedent for such suspicion; this logic plays out with the oeuvre of artists like Van Gogh, who didn’t sell a single painting in his lifetime. He created in a vacuum, untouched by deadlines, sales expectations, or commercial demand. He wasn’t forced to cheap concessions to sell, as is so often done now this Christmas time. There were no elves breathing down his neck.

Even on the flipside, Mark Rothko notably rejected the one and only commission in his life at the four seasons restaurant, declaring ‘Anybody who will eat that kind of food will never look at a painting of mine’. Even royalty of international galleries and auction houses fear the damaging impact of creating art for mass commercialism.

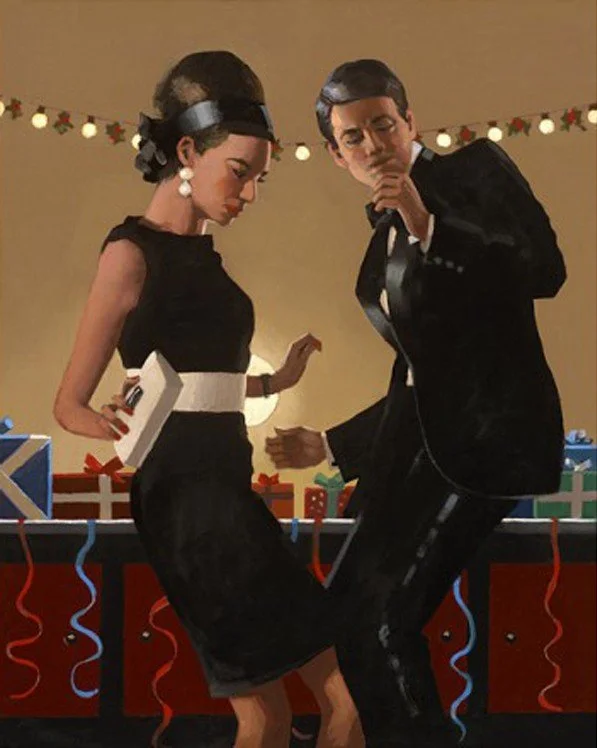

Jack Vettriano, Let’s Twist Again, 2010, Oil on canvas, 38 x 30 cm.

Image Courtesy of Jack Vettriano.

Closer to home in Scotland, Fife has its own exemplar of this repression: Jack Vettriano. The self-taught artist, despite being rejected from the Edinburgh school of art, has struck great international success, particularly around Christmas. His scenes appear on many of our festive cards here in Scotland, even used as the First Minister’s Christmas card in 2010 showing Scots amid their celebrations.

However, his success comes with scathing criticism. The Guardian’s Jonathan Jones mocked Vettriano’s work as ‘popular with “ordinary people” who buy reproductions of his pseudo-1930s scenes of high heeled women and monkey suited men, and celebrities who fork out for the originals of these toneless, textureless, brainless slick corpses of paintings’.

Such hostility highlights the concern at hand: that mass production can cheapen artistic value. Christmas is a time where this anxiety is at its height, with its insatiable appetite for visual culture. Some might say this holiday facilitates this hostile artistic practice, leading to a stifling in creativity.

Yet, is this fair? Such accusations of ‘brainlessness’ regarding how Vettriano mimics other artists is a redundant one, for where would Lichtenstein and Warhol fall in the art historical canon? Even Raphael had a sneaky look at Michelangelo’s sketchbook while working in the Vatican — it is part of the artistic process.

However, here’s the irony - Scotland once censored Christmas for being too indulgent, too fun, in the name of religion. Now in a capitalist epoch, the art of Christmas may be suppressing creativity in a similar way, but for radically different reasons. Reaching a quasi-puritanical nightmare, we have almost turned full circle from religious repression to commercial repression. Both however are suboptimal conditions for the production of art, to say the least. Today, neither God nor art are revered appropriately, in an idolatry of the kitsch. Are we seeing art’s authenticity steering too far astray?

Not necessarily. Although commercialisation may alter creativity, it does not make it ‘brainless’. Yuletide remains a stellar opportunity for the artisan, where Christmas markets and local makers from independent studios have far greater chance to craft and sell their work. Buying from them can reignite the authenticity of Christmas art, rather than putting fuel on the corporate conveyor belt in our high streets.

The answer is not to ban Christmas like the Presbyterians, of course, but indeed to reclaim it by investing festive budgets into those who challenge such corporate clichés with fresh holiday-handiworks.

Bibliography

Cain, Abigail. “Why One Meal Made Rothko Cancel His First Major Commission.” Artsy. November 18, 2016. https://www.artsy.net/article/artsy-editorial-why-one-meal-made-rothko-cancel-his-first-major-commission.

Jack Vettriano. “First Minister’s Christmas Card — Jack Vettriano.” Jack Vettriano, December 6, 2010. https://www.jackvettriano.com/first-ministers-christmas-card/.

Jones, Jonathan. “A Picture of Poor Taste.” the Guardian. The Guardian, October 5, 2005. https://www.theguardian.com/culture/2005/oct/05/1.

Lill, Isabella, and Griffin Pion. “Debate: ‘Commercialism Ruins Art.’” The Oxford Student, February 20, 2019. https://www.oxfordstudent.com/2019/02/20/debate-commercialism-ruins-art/.

MacPherson, Hamish. “Why Christmas Was Banned in Scotland for Four Centuries - and How That Changed.” The National, December 23, 2021. https://www.thenational.scot/news/19803443.christmas-banned-scotland-four-centuries---changed/.

McLean, Pauline. “Jack Vettriano: Back in Kirkcaldy Galleries That Inspired First Sketches.” BBC News, June 17, 2022, sec. Scotland. https://www.bbc.co.uk/news/uk-scotland-61838298.