Rashid Rana’s “Veil” Series, 2004

Rashid Rana, Veil I/2/3, 2004. C-Print + DIASEC, 51x51cm

By Lily Spencer

Rashid Rana is considered Pakistan’s most influential contemporary artist. He was born in 1968 in Lahore and is the fifth son of a policeman. Despite pressure to pursue a more practical career, such as medicine, the army or the civil service, Rashid attended the National College of Art in Lahore. He later studied at the Massachusetts College of Fine Arts in Boston and is currently the head of the fine art department at Beaconhouse National University in Lahore. His significance was made concrete when he was made a solo exhibitionist for the Pakistan pavilion at the Venice Biennale in 2015. In his art he explores concepts around the globalising modern world, its contradictions and society’s representation of particular groups.

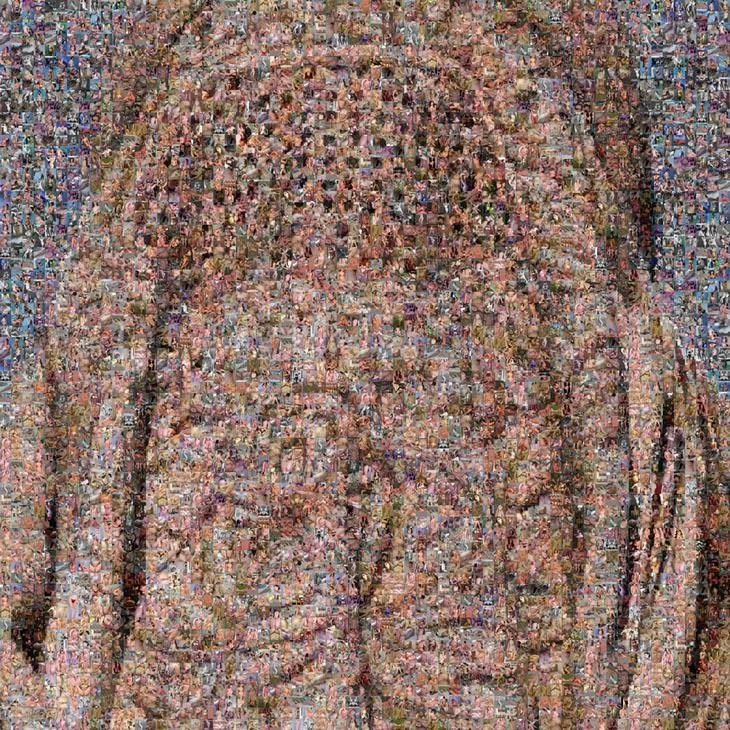

His most famous pieces, and the ones I will focus on in this article, are those from his “Veil” series. These prints depict a seemingly pixelated image of an anonymous woman wearing a burqa (the veil that covers the entire face of a woman, most commonly associated with Islam). On closer inspection, however, it is revealed that these images are in fact micro-mosaics built of tiny stills of women, taken from hard-core pornography. While this juxtaposition may seem simplistic, it can be viewed and interpreted from several different perspectives.

Most obvious seems to be the feminist interpretation, as the image presents a stark juxtaposition between the two most extreme representations of women’s sexuality. The image depicts two extreme forms of damaging female oppression within society, that of the control of women’s bodies and clothing through religion and that through the pornography industry. Both forms of control and oppression, while they look like opposites, essentially have the same effect in disallowing female bodily autonomy. The prints are also a visual representation of the virgin/Madonna-whore complex. By engaging with this, he presents a woman, whose body is entirely covered, angelically avoiding being provocative to men, however, she is made up of thousands of images of women in highly provocative dress and positions.

This is complicated, however, by the political and religious connotations of the burqa. Could this be an accusatory image, addressed to devoutly Muslim men, regarding the way they see women? If not covered, then a whore? Or, through post-colonial discourse, is this revealing the contradictory images men from the Western ex-colonial powers have and have had of women in the Middle East? In his seminal work, Orientalism, Edward Said discusses the negative and simplistic representational dichotomy that Western writers have used to depict women in the Middle East. Either they were depicted as highly sexualised and exotic, used to symbolise the West’s hedonistic fantasy of the Orient, or they were helpless victims of the oppressive, violent and corrupt Muslim men – those the Empires sought to civilise. These pieces gain even more meaning and significance in our contemporary context, particularly regarding our so-called “post-truth” era. Rana presents rigid, simplified and extreme stereotypes of women, race and religion, juxtaposing their supposed opposing views and representations. He draws attention to the judgements and prejudices of the viewer, both Western and Middle Eastern, male and female, and how media and social imagery has warped our ideas around gender, dress and oppression.

The piece’s description in its profile on the Saatchi Gallery website asserts that, through these pieces, Rana encourages us to ‘critique the so-called machinery of truth from which [these images] are born.’ These pieces are fascinating because they become more complex and nuanced the more they are looked at and their meaning alter through time and space. They would have different resonances and meanings depending on whether they were exhibited in London, Lahore, other parts of the Middle East or India (where Rana has spent much of his career). It is provocative, controversial, accusatory, brash, but somehow, at the same time, gentle and beautiful.

Rashid Rana, Veil I/2/3, 2004. C-Print + DIASEC, 51x51cm

Rashid Rana, Veil I/2/3, 2004. C-Print + DIASEC, 51x51cm

notes

Doshi, Riddhi. “Rashid Rana: Lifting The Veil.” Hindustan Times. Last updated 1st Apr. 2012. Accessed 27th Feb. 2017.

http://www.hindustantimes.com/art-and-culture/rashid-rana-lifting-the-veil/story-QvJUDZUQDtOA5jYLveso0J.html

Lisson Gallery Website. “Rashid Rana.” Accessed 27th Feb. 2017. http://www.lissongallery.com/artists/rashid-rana

Saatchi Gallery Website. “Rashid Rana.” Accessed 27th Feb. 2017. http://www.saatchigallery.com/artists/rashid_rana.htm?section_name=new_india

Saatchi Gallery Website. “Rashid Rana, Veil Group.” Accessed 27th Feb. 2017. http://www.saatchigallery.com/artists/artpages/rashid_rana_veil_group.htm

Said, Edward W. Orientalism: Western Conceptions of the Orient. London: Routledge and Kegan Paul Ltd, 1978.