The Poetics of Paul Delvaux

By Nicole Entin

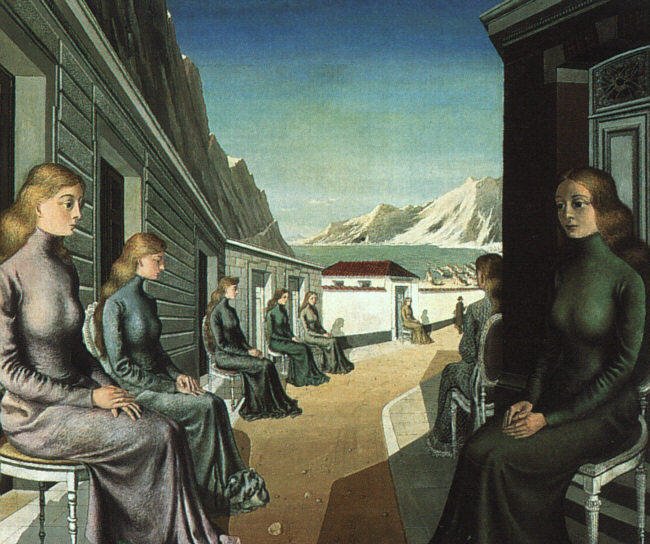

Can a poem be a piece of visual analysis? Lisel Mueller’s ekphrastic poem Paul Delvaux: The Village of Mermaids, Oil on canvas, 1942 suggests that the exploration of meaning in a painting does not necessarily have to be set down in prose. Her methodical free verse attempts to make sense of an enigmatic painting by the Belgian painter Paul Delvaux [Figure 1], in which a row of sombre, soberly-dressed women line the road of a coastal village:

“Who is that man in black, walking

away from us into the distance?

The painter, they say, took a long time

finding his vision of the world.

The mermaids, if that is what they are

under their full-length skirts,

sit facing each other

all down the street, more of an alley,

in front of their gray row houses.

They all look the same, like a fair-haired

order of nuns, or like prostitutes

with chaste, identical faces.

How calm they are, with their vacant eyes,

their hands in laps that betray nothing.

Only one has scales on her dusky dress.

It is 1942; it is Europe,

and nothing fits. The one familiar figure

is the man in black approaching the sea,

and he is small and walking away from us.”

[Figure 1] Paul Delvaux, The Village of Mermaids, 1942, oil on panel, 104.3 x 124.1 cm.

Mueller’s poem successfully identifies key compositional aspects of Delvaux’s painting including the tension between the stillness of the foreground and subtle indications of movement in the background, the oblique perspective of ‘the street, more of an alley’, the unknown identities of the seated women, and highlights the figure of ‘the man in black approaching the sea’, his back turned to the viewers of the painting. The strengths of a poetic analytical framework to both define and reveal the ambiguity of Delvaux’s symbolism-rich and allusion-laden works are not only undeniable, but perhaps even advocated for by the artist himself. In characterising the Surrealist movement with which he has often been connected as ‘a reawakening of the poetic idea in art’, does Delvaux implicitly suggest a return to the subjective free-association that is characteristic of poetry in order to examine the strange and uncanny dreamscapes of his painting?

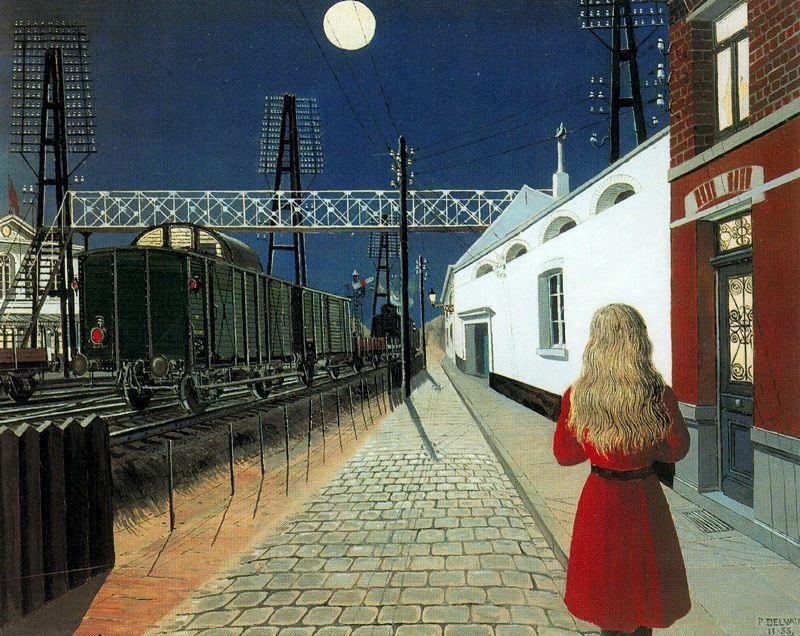

The paintings of Paul Delvaux are filled with ethereal women, haunted looks in their eyes that alternatively pierce or avoid the viewer’s gaze, disjointed and unreal fragments of classical buildings, deserted streets in the night-time, reflections in mirrors that reveal something outside of the pictorial space. A graduate in Classics turned painter, he depicts Greek temples, Vestal Virgins, Penelope on the shores of Ithaca in a deep violet gown. Yet his oeuvre spans from antiquity to the industrial age, with several paintings featuring trains and trams in moonlit, almost empty stations and roads – reflecting his childhood fascination with locomotives, and leading him to be named honorary stationmaster of a university town in Belgium.

[Figure 2] Paul Delvaux, Solitude, 1955, oil on wood panel, 99.5 x 124 cm, Collection of the Belgian State, Brussels.

From this rather freewheeling description of Delvaux’s works, it is evident that he is an artist who is hard to pin down. He rejected associations with the Surrealists, though acknowledged the influences of René Magritte and the metaphysical painter Giorgio de Chirico on his style. He paid homage to writers ranging from Homer to Jules Vernes [Figure 3]. Yet, much like Freud’s proposition in The Interpretation of Dreams that deciphering the images of dreams can reveal a ‘poetical phrase of the greatest beauty and significance’ behind a seemingly incomprehensible narrative created within the unconscious, the symbolic imagery within the dreamscapes of Delvaux’s paintings can be similarly interpreted to discover their inherent poetics.

[Figure 3] Paul Delvaux, Tribute to Jules Verne, 1971, oil on canvas, 150 x 120 cm.

A shared, central characteristic of poetry and dreams that is also present within the paintings of Delvaux is the notion of interconnectedness. Poetic tradition forms networks of influence and allusion between poems written in different centuries and by different authors. In comparison, dreams often have motifs that recur in different forms across time and modified by their context. These ideas of interconnected motifs can aid in reading across Delvaux’s body of work, which reinterprets literature and history while often exploring the same concept or composition from several perspectives.

Returning to his Village of Mermaids, the figure of the ‘man in black’ in the background of the work provides a potential starting point for a poetic reading of the painting and its place within Delvaux’s oeuvre. In his bowler hat and dark overcoat, the man in black seems to be the most tangible visual link to Delvaux’s contemporary present of the mid-twentieth century. About to turn the corner and exit the pictorial space, he urges the painting’s viewer to follow after him. At the same time, while he draws the viewer forward, is he also being called into the distance by the mermaids – or ‘sirènes’ – on the beach? Are the mermaids perhaps a symbol themselves, perhaps of the contemporary context of the second World War that called men from their homes and into battle? The question of whose agency controls the visual narrative presented in the painting is thus raised in Delvaux’s ambiguous composition.

Five years after The Village of Mermaids, and three years after Belgium was freed from German occupation in 1944, Delvaux reinterprets the work in his monumental The Great Sirens [Figure 4] of 1947. Seated women line the left side of the composition, but rather than clothed in tight, dark dresses that cover their arms and necks, the women are half-nude, elaborate crowns of jewels, feathers, and flowers atop their heads, in front of a Neo-Classical arcade rather than a modest row of village houses. The shore, this time, is closer to the foreground, and the sirens on the beach raise their arms in an invocation to the ocean. One is turned away from her sisters, towards the man in black, who appears once more in this iteration of the composition. Why has this change in style and perspective occurred, recontextualising the scene from The Village of Mermaids in a more ambiguous visualisation of a fantastical past? Does The Great Sirens show the viewer what happens if they follow the man in black around the unseen corner of The Village of Mermaids? Or does its parallel composition depict another dreamlike world beneath the unsettling mundanity of the first?

[Figure 4] Paul Delvaux, The Great Sirens, 1947, oil on masonite, 3.05 x 2.03 m, Metropolitan Museum of Art, New York.

This, in my opinion, exemplifies the ‘poetic mode’ of analysis that this short piece has been striving towards. Revelling in the subjectivity of interpretation, Delvaux’s paintings – like poems – inevitably raise more questions than are answered. Just as Lisel Mueller writes that ‘the painter [...] took a long time / finding his vision of the world’, so too, perhaps, can art historians take time in finding their vision of Delvaux’s world.

Notes:

Freud, Sigmund. The Interpretation of Dreams. Translated by James Strachey. New York: Basic Books, 2010.

Klingsöhr-Leroy, Cathrin. ‘Paul Delvaux: Dawn Over the City’. In Surrealism, 46-47. Los Angeles: Taschen America, 2006.

Mueller, Lisel. Paul Delvaux: The Village of Mermaids, Oil on canvas, 1942.