Penelope and the Suitors Weaving, Femininity, and Ancient Myth

By Claire Ferguson

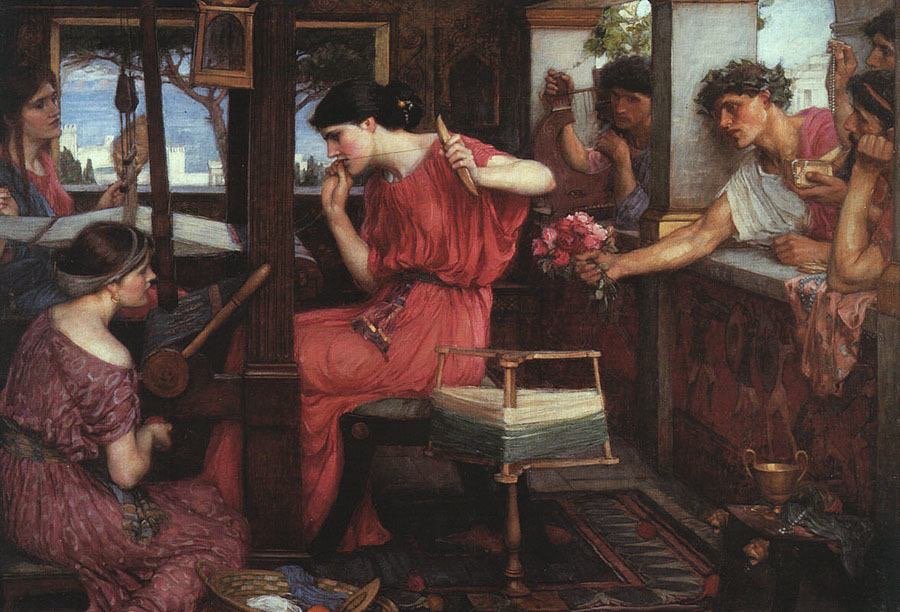

Penelope and the Suitors, 1912, by John William Waterhouse depicts a domestic interior in ancient Ithaca. A central female figure, dressed in red, is seated at her loom. She is joined by two maids who aid her in her weaving. They are each dressed in vibrant fabrics and adorn themselves with accessories. The protagonist turns her back to an open window. Peering through, lean a group of male figures. They are vying for her affection. Three of the suitors present a lyre, a bouquet of flowers, and a gold jewellery box, with the fourth visitor arriving empty-handed and merely ogling. The women continue their work, refusing to engage. Just below the window, within the interior, lies a battle frieze and the room is otherwise fashioned with a gold lantern, a basket of yarn, and a gold chalice. The central figure is interrupted at her work, subject to the intrusion of clearly unreciprocated attention. There is an apparent hierarchical composition between the seated female figures and standing male suitors, creating great contrast between the movement of these groups of figures. The women remain docile, intent on completing their task, while their visitors lunge into their workspace, readied. At first glance, these suitors appear to be in a position of authority. Their intrusion is acknowledged by the central figure, whose gaze wavers ever so slightly.

The act of textile weaving offers an additional gendered interpretation of the scene. Her suitors, who offer flowers and jewellery, serve to reinforce the association of femininity and self-presentation. By contrast, Waterhouse offers no emphasis on the presentation of the male figures in Penelope and the Suitors. Rather, they are relatively unadorned and are privileged in their ability to remain unseen. Their female counterparts, however, are denied such visibility and instead exist as objects for possession. This extends, furthermore, to the habit of dismissing female clothing with vanity and excess – and, by the opposition, male clothing with functionality and integrity. Feminine associations of ornament, fabric, and the production of cloth also invoke fears of masks and deception.

The association of women and cloth, furthermore, evokes associations of weaving as an art of deception. Ovid’s Metamorphoses tells the myth of Arachne, a talented woman who was challenged by Athena to a weaving competition. Arachne chose to create a tapestry which disparaged the gods, presenting their brutality. Her subversion is punished by the gods - she was transformed into a spider, fated to weave webs for all eternity. Waterhouse’s painting evokes a similar mythological tale. The woman in red is the Queen of Ithaca, as presented in Homer’s Odyssey. She is the wife of Odysseus. While her husband is away, the throne of Ithaca remains vulnerable. Sensing opportunity, she is thwarted by many male suitors. Penelope and the Suitors captures her artful moment of deception. Unbeknownst to the male figures in this painting, the tapestry thread held between Penelope’s teeth is about to be severed; thus, denying their wishes. The queen was able to deter her admirers by insisting on the completion of an intricate weaving project. During the evening, however, Penelope unbound her progress, thereby extending her autonomy. Furthermore, the battle frieze which lines the wall of Penelope’s workspace foreshadows the fate of the men. Upon Odysseus’s return, they will be killed for their actions. Her trick was first discovered by Antinous, who revealed:

“So by day she’d weave at her great and growing web –

by night, by the light of torches set beside her,

she would unravel all she’d done. Three whole years

she deceived us blind, seduced us with this scheme.

”

Penelope and the Suitors can be reinterpreted in this context. The queen’s male visitors, though dominant in their position, remain unaware of their impending fate. Penelope leans over her workspace, not to cower, but rather to conceal her act of self-preservation. Gazing to the side, she acknowledges her surroundings, and proceeds with her precarious act of deception. The dynamic of power within this composition is much more complex than what first meets the eye. Waterhouse utilizes ancient myth to present a complication of cra and gender norms. His painting celebrates Penelope as a symbol of fidelity and virtuosity. Completed in England during WWI, Penelope and the Suitors can be seen as resonant in a wartime context. The painting may provide commentary on the transformation of domestic roles as men were sent off to battle. Waterhouse offers a celebration of the steadfastness and loyalty of women on the home front.

John William Waterhouse, Penelope and the Suitors, 1912, oil on canvas.

Notes:

Aberdeen Art Museums. ‘Penelope and the Suitors by John William Waterhouse.’ 8 September 2020, Youtube, https://www.youtube.com/watch?v=FqnoZz7axjg [Accessed 1 May 2023]

Cavallaro, Dani and Warwick, Alexandra. ‘Surface/Depth - Dress and the Mask.’, In Fashioning the Frame: Boundaries, Dress and Body (Oxford; New York: Berg, 1998): pp. 128-156.