Art Versus Valentine’s Day

By Martyna Majewska

As I am writing, Valentine’s Day is drawing to a close, but I still feel brainwashed by the flood of romantic imagery that doesn’t let me think about anything else. Right, anything else but what? Love?

Not exactly. If you’re in love, I doubt that V Day might intensify the feeling. If you’re longing for love, it’s likely to give you either spasms of laughter, or depression, depending on the level of your desperation. This day (I should probably include the entire week leading up to it as well) makes me ponder how love is represented? Obviously, I could go on and on about computer graphics, food presentation, and wrapping paper design, but for the purpose of this blog, it’s best if I focus on “fine” art. What makes an artwork about love powerful and compelling? Can art reduce love to a commodity? Are there any artworks that speak of love wisely?

Before I discuss powerful and interesting love-related or love-inspired art, I shall begin by explaining a few pieces that fail to convince me. Perhaps the easiest way to do that is to open Jeff Koons’s catalogue raisonné. Koons’s renditions of the theme in question seem to constitute the quintessence of the sort of tacky, “commodified” love that Valentine’s Day tends to promote. On the one hand, we could easily dismiss his work as trivial and silly, while on the other hand, it actually exposes the idea of “love” that the media and marketing specialists have instilled in us.

Jeff Koons, Hanging Heart

If there is one work of art that says love more explicitly – or more literally – than others, it must be Robert Indiana’s LOVE. As a piece of design, it’s brilliant in its simplicity. It’s huge, it’s bold, it’s also very American. However, like in the case of Koons’s Hanging Heart, there’s something rather annoying about Indiana’s sculpture: it is everywhere. Its ubiquity and iconic status have made it not just commonplace but also transparent. Furthermore, everyone can get a copy in a variety of forms: key rings, magnets, T-shirts, you name it. One could argue that you can never have enough love, you can never say “I love you” too many times, but at the same time the messages communicated by Pop repetition are never hopeful: all that Pop Art takes on board is for sale, and all of its subjects are perishable.

LOVE sculpture by Robert Indiana, on the corner of 6th Avenue and 55th Street in Manhattan, NY. Hu Totya - Own work

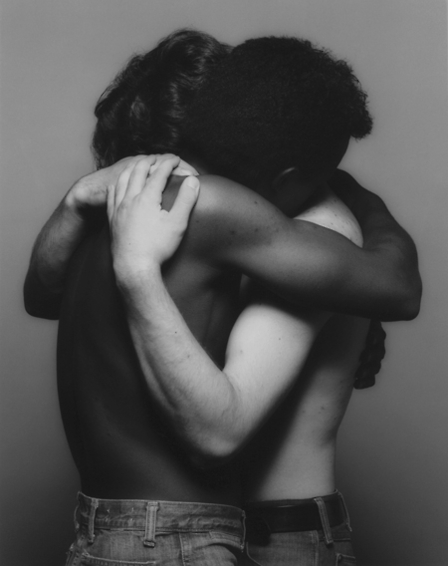

Robert Mapplethorpe, Embrace, 1982

Let me go back to Koons, whose Made in Heaven series proves that images of love, and especially of love-making, remain exciting, even in the age of unprecedentedly accessible pornography. Countless books and essays have been published on erotic art and I do not wish to explore this topic here, yet I would like to emphasise how powerful this genre is and has been. Certainly, images of the consummation of love can take the grotesquely vulgar form that Koons insists on. In those cases, love is reduced to a shock-inducing controversy. Yet artworks picturing intimacy can also challenge all kinds of stereotypes and social norms. For example, one might be surprised that some of the Japanese shunga prints, which display (often in the most graphic ways) extremely creative approaches to sexual intercourse, were made as early as the seventeenth century. Robert Mapplethorpe’s Embrace demonstrates that artists can use their work to change how we conceptualise love: his photograph reminds us that there is no fixed image or definition of love, though not everybody is willing to accept it.

Jeff Koons, Jeff and Ilona (Made in Heaven)

Sugimura Jihei (active c. 1681-1703) Three Lovers Japan, Edo period (1615-1868), mid 1680, Woodblock print; ink on paper with hand-coloring, Gift of James A. Michener, 1972(16270)

Of course, love is not always hugs and kisses, and the misery that it often brings has been an extremely fertile ground for artists since time immemorial. I recently saw an exhibition of Munch’s prints at the Albertina in Vienna and, I must say, his is probably the most saddening vision of love in the history of art. I would even venture a claim that a visit to such an exhibition is a perfect cure for the lonely: it can put you off love for a very long time. Munch’s sickening images of love seem to be infused with an almost palpable melancholia, and some of his works make it rather clear that the demon responsible for his romantic failures is female. For this reason, it should be interesting to look at how love has been portrayed from the often- overlooked female viewpoint. Carrie Mae Weems’s Kitchen Table Series presents a much more down-to-earth – if not downright pragmatic – narrative of love, from courtship to breakdown, making love appear less exciting than Koons, less mystic than Munch, but certainly more real.

Edvard Munch, The Vampire, 1895 (printed 1896/1902) lithograph and color woodcut with watercolor on thick china paper. National Gallery of Art, Washington, Ailsa Mellon Bruce Fund and Gift of Lionel C. Epstein

Carrie Mae Weems, Untitled (Man reading newspaper) from Kitchen Table Series, 1990. Promised gift to the Art Institute of Chicago.

I could discuss any number of artworks to do with love (I hope nobody will blame me for not evoking Klimt’s or Rodin’s Kiss), yet a survey of art about love was never my intention. I wished to demonstrate rather that there is more to portraying love than the cartoons, GIFs, and gift-wrapped facebook messages that we were forced to look at this weekend. The trigger that made me think of all the ways in which love can be visually conveyed was Felix Gonzalez-Torres’s Untitled (Perfect Lovers). It may be one of the most beautiful works about love that I have ever seen but, then, I guess that’s the thing about love: we all see it differently.

Felix Gonzalez-Torres. Untitled (Perfect Lovers). 1991. Clocks, paint on wall. The Museum of Modern Art, New York. Gift of the Dannheisser Foundation © The Felix Gonzalez-Torres Foundation, New York