The Aesthetics of Stillness and Spectacle: How Chinese Film Techniques Mirror Contemporary Chinese Art

By Alix Ramillon

Over the last twenty years, Chinese cinema has emerged as a vital space for examining the nuanced aesthetic, philosophical, and political dimensions of contemporary Chinese artistry. Renowned filmmakers like Zhang Yimou, Jia Zhangke, Bi Gan, and Wang Bing have successfully merged time-honoured aesthetic principles with innovative digital techniques, creating visual expressions that resonate within both the artistic landscape of the People's Republic of China and its global diasporic communities. Recent offerings, including the 2023 film Escape Into the 21st Century, further this heritage by exploring the complex technological, political, and cultural dichotomies of modern China through a strikingly visual, phenomenological approach.

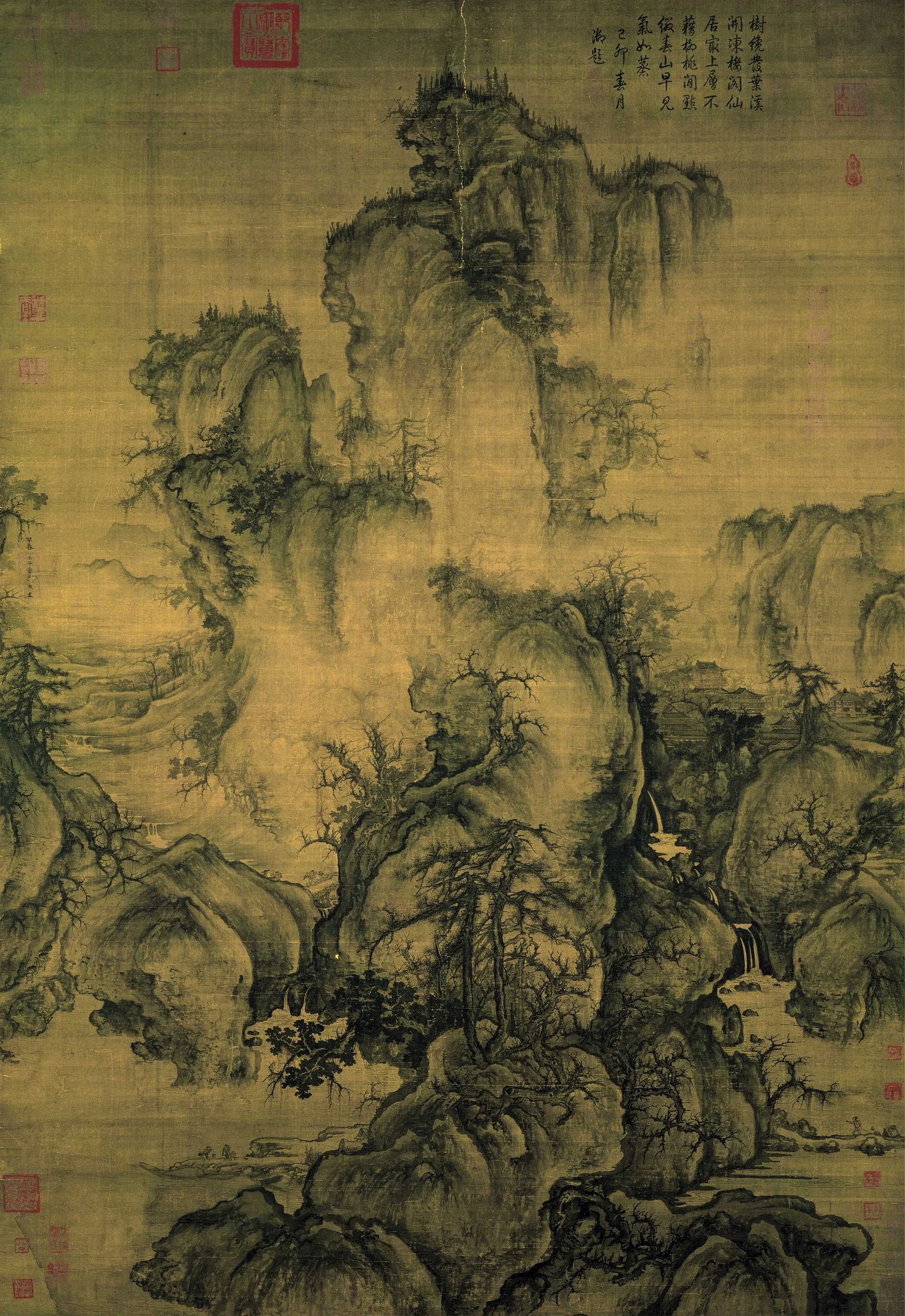

The concept of landscape framing (山水结构) stands out as one of China's most persistent aesthetic traditions. Contemporary filmmakers reinterpret classical compositional elements in the cinematic realm through expansive negative spaces, atmospheric perspectives featuring mist, depth, and multi-layered horizons, and prolonged shots of mountains, water, and historical ruins, highlighting humanity's modesty amidst nature.

Moreover, the cinematic techniques found in Chinese film, characterised by slowness, spectacle, landscape composition, and heightened digital aesthetics, exhibit a significant continuity with current artistic practices in China. These methods underscore how Chinese artists navigate the disjunctions arising from modernisation, technological advancement, social disintegration, and the evolving landscape of national identity.

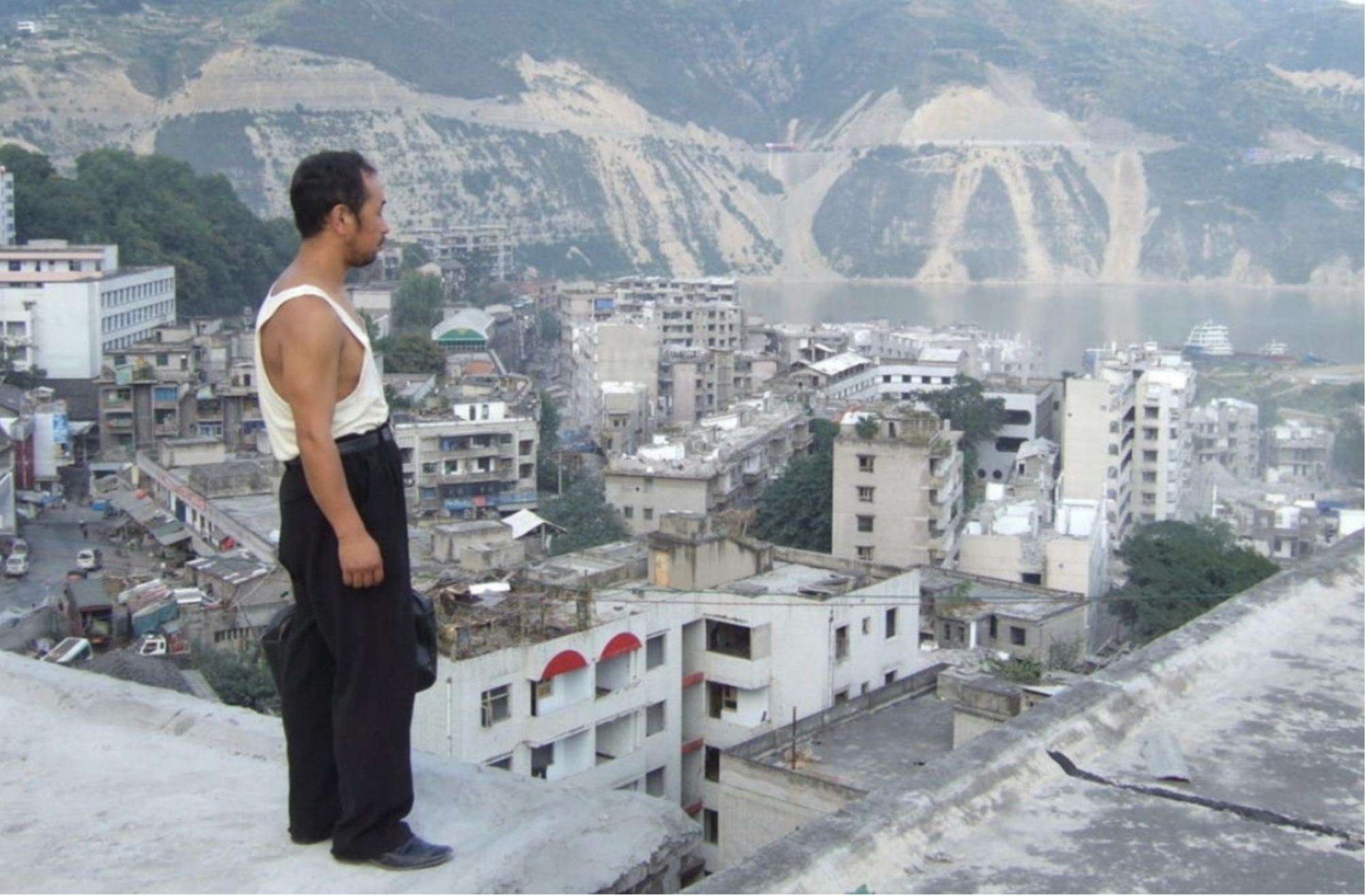

Film still from Jia Zhangke, Still Life (Sanxia Haoren), 2008.

Image courtesy of Google Images

Guo Xi, Early Spring, c. 1072, Northern Song Dynasty.

Image courtesy of the National Palace Museum, Taiwan.

Chinese “slow cinema” often serves as a counterbalance to the rapid pace of modernisation in the region. The extended takes, stationary shots, and reflective silences showcased in the works of directors such as Bi Gan, Wang Bing, and Jia Zhangke mirror the contemplative rhythms of ink landscape painting (山水画), which emphasises atmosphere, emptiness, and the perception of time, as developed during the Tang dynasty. There is a clear parallel between the mountainous nature of the ink paintings and the urban landscape, yet the incorporation of technological life is evident.

Yang Fudong, Seven Intellectuals in a Bamboo Forest, Part I, 2003.

Image courtesy of Google Images.

This cinematic slowness mirrors the aesthetics of contemporary artists such as Yang Fudong, whose black-and-white multi-screen installations echo the contemplative poetics of classical ink painting.

Escape Into the 21st Century intricately weaves together its focus on human stories with grandiose displays of infrastructure, including high-speed railways, sprawling data centres, towering empty skyscrapers, and vibrant neon cityscapes. It serves as a critique of the perceived aesthetics of progress, unearthing the psychological tensions that underpin China's techno-utopian aspirations.

In this way, the film both embraces and deconstructs the concept of spectacle: while the camera emphasises the majesty of infrastructure, it also brings to light the individuals who remain overshadowed by it. Its visuals dance between classical beauty and cyberpunk edge, depicting industrial ruins akin to shan shui mountains, neon ads casting a glow on dark riverbanks, and drones capturing viewpoints reminiscent of traditional scroll paintings, all while dwarfing characters with colossal, unfinished projects. These striking contrasts forge a modern shan shui, amalgamating natural vistas with artificial landscapes. Rather than choosing between the legacy of tradition and the allure of the future, the film suggests that China's current visual identity thrives in its intersection.

Film still from Yang Li, Escape from the 21st Century, 2024.

Image courtesy of Google Images.

Employing slow tracking shots and prolonged observational moments, the film reveals how marginalised communities adapt to rapid urban change. Rather than focusing on a conventional narrative, it invites viewers to immerse themselves in the richness of lived experience, a central feature that resonates in contemporary Chinese video art and documentary realism. This approach aligns with the broader philosophical ideas of “empty-full” (虚实) aesthetics, where the spaces and omissions hold just as much weight as what is displayed. The emphasis on slowness becomes a powerful statement that resists the relentless pace of technological capitalism. While slowness represents one facet of Chinese visual culture, the spectacle embodies another. China harnesses striking imagery, including choreographed crowds, vibrant colours, and precise compositions, to project a facade of national unity and modern advancement.

Gu Wenda, Installation view of ‘Central Park’ at Chambers Fine Art, 2013.

Image courtesy of New York Art Tours.

Similar to Artist Gu Wenda, who reworks traditional landscape motifs through digital and conceptual practices. His “ink-wash aesthetic” has re-emerged in virtual reality, AI-generated imagery, and large-scale installations. Thus, a central theme in recent Chinese cinema and art is the surveillance gaze, namely the idea that images are now produced by machines, state infrastructures, and algorithmic systems rather than individuals.

The film Escape Into the 21st century by Yang Li incorporates crowdsourced smartphone footage, algorithmically stitched images, scenes filmed in the style of CCTV archives, digital overlays simulating facial recognition patterns, and a meta-narrative about being “seen” in a techno-political landscape. This approach blurs the line between fiction and documentary, human and machine vision, a significant trend in both film and Chinese media art. The film’s hybrid visuality suggests that contemporary Chinese subjecthood is mediated through digital systems, making technology both a tool and a character.

Bibliography

Xiang Fan, “Contemporary Art Cinema Culture in China”, Bloomsbury Academic, 2024.

Cath Clarke, “Escape from the 21st Century review – teenagers fast-...”, The Guardian, February 18, 2025.

Stefano Veg, “From Documentary to Fiction and Back,” China Perspectives, no. 2007/3, 2007.