The Treachery of Reality: Magrittean Echoes in Peter Weir’s The Truman Show

By Grace Liang

René Magritte, The False Mirror, 1929, Oil on canvas, 54 x 80.9 cm.

Image courtesy of MoMA.

The Truman Show (1998) explores how far society can take its voyeuristic desire for mimesis in its storytelling. The manipulation of media and the constructed reality of Weir’s film are better understood through the thematic framework of Belgian surrealist René Magritte's paintings. His masterful use of visual paradox pushes the boundaries of perception, echoing Weir’s commentary on media manipulation and the construction of reality. Together, the artists explore the disturbing disparity between appearance and reality, creating visual metaphors that seek to unmask the artificial nature of our perceived world.

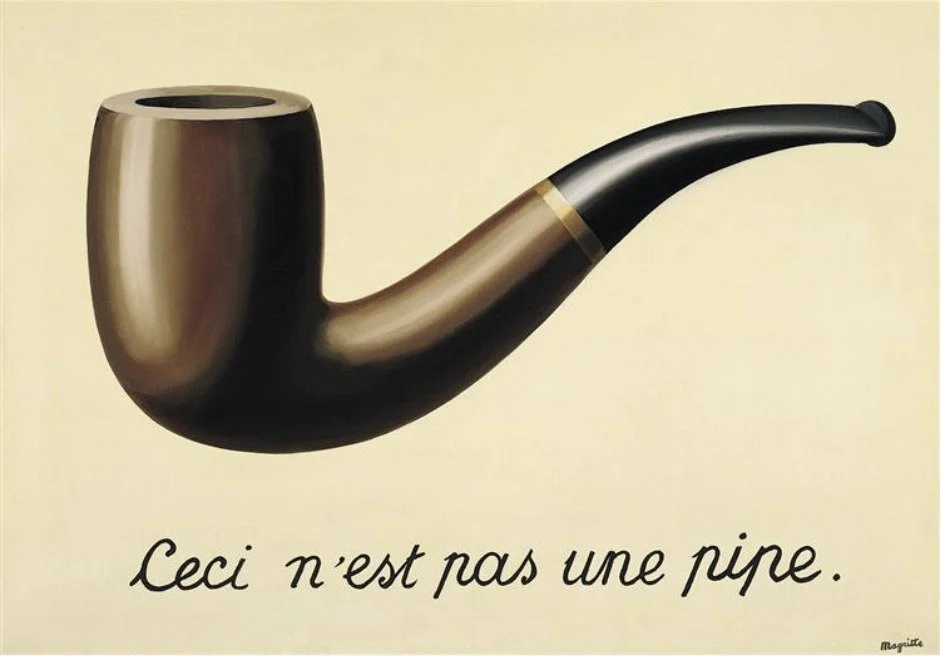

René Magritte, The Treachery of Images, 1929, Oil on canvas, 63.5 x 93.98 cm.

Image courtesy of WikiArt.

Magritte’s pristine domestic scenes blend right in with the utopian suburban aesthetics of the island of Seahaven. The town is populated by actors masquerading as Truman’s friends, family, coworkers, and neighbors. The set is rigged with countless hidden cameras, all of which feed back to the control center in the sky-painted dome. Truman exists within a subverted panopticon, under constant surveillance by an all-seeing eye in the sky, reminiscent of Magritte’s The False Mirror (1929). The title hints at the fallibility of our vision. The idea that we cannot put complete faith in our eyes to accurately represent reality is central to many of Magritte's works. In an exaggerated parallel, Truman, too, cannot trust anything he sees; even the sky is fake. Both Seahaven and the world of Magritte’s paintings create an uncanny valley effect, where a fundamental wrongness keeps them just shy of appearing real. One of Magritte’s most well-known works is The Treachery of Images (1929), a painting of a pipe above the text “Ceci n'est pas une pipe” or ‘This is not a pipe’. The artist sought to subvert expectations of representational painting by making clear that a painting of a pipe is not an actual pipe. In the same way, Seahaven’s representation of a neighborhood is not a neighborhood, and Truman’s pantomimed relationships are not relationships. The only thing that is genuine and authentic is Truman (the ‘True Man’) himself.

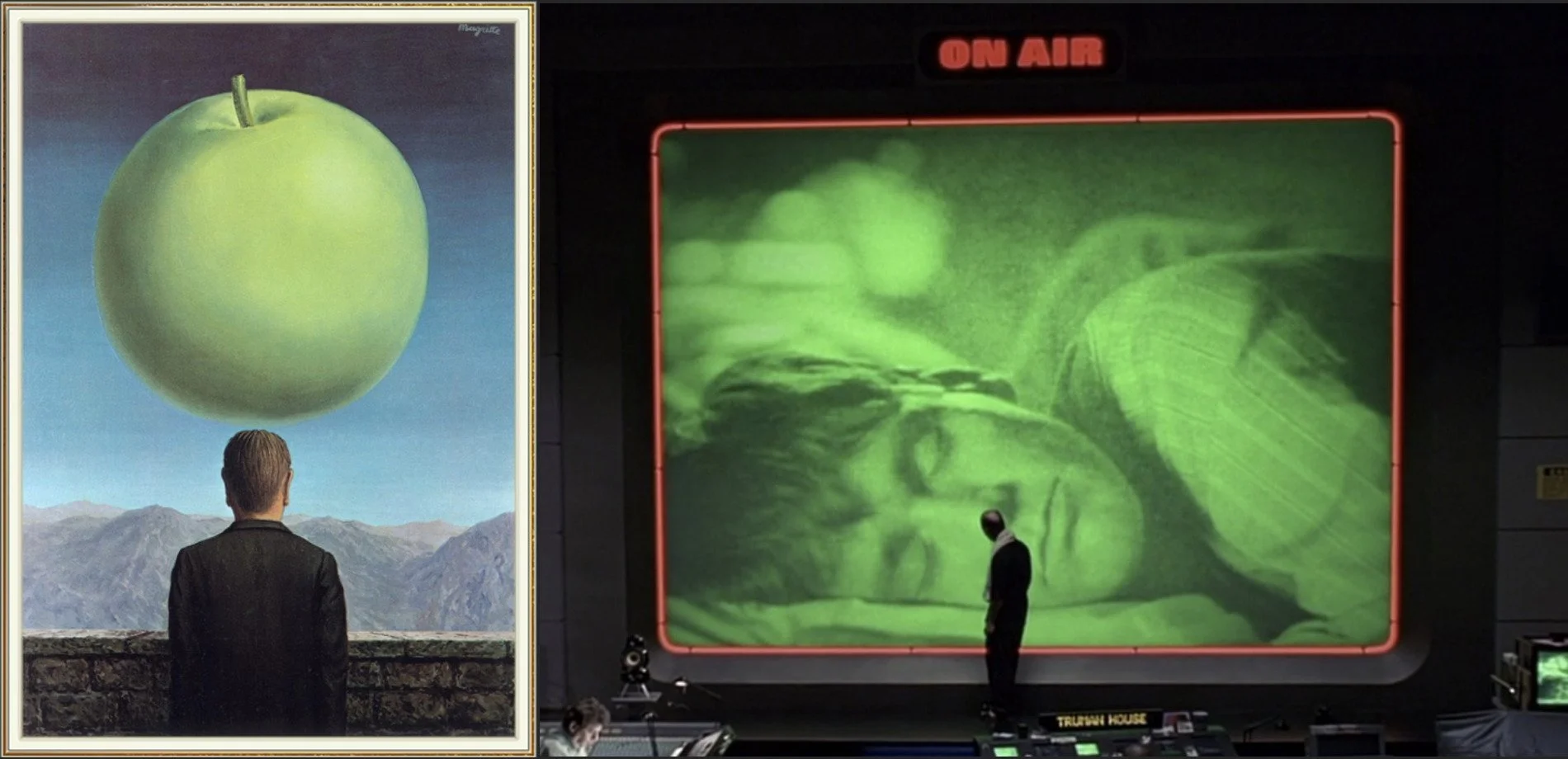

(left) René Magritte, The Postcard, 1960, Oil on canvas.

Image courtesy of WikiArt.

(right) Still from Peter Weir, The Truman Show, 1998.

Image courtesy of Evan E. Richards.

The question of authenticity and representation is further complicated by the fact that Truman himself has become an image to be consumed. Outside of his fabricated reality, he is reduced to a mediated spectacle controlled by an unseen creator. The relationship between observer and observed is a central theme in both Magritte’s The Postcard (1960) and the still above from The Truman Show. Both images depict a man in dark clothing, standing contemplatively before a larger-than-life green object. In The Postcard, Magritte plays with the scale of one of his signature green apples as Christof gazes at the digitally enlarged Truman. For Magritte’s figure, the apple commands his attention, turning him away from the viewer and thereby obscuring his face. His most individual features are hidden, denying any potential for human connection as the apple replaces his identity and personhood with a symbol. In the still from The Truman Show, the eerie glow of the screen creates a barrier between the man and the showrunner, with Truman’s humanity filtered through the pixels. It is perhaps the fact that Christof has exclusively experienced Truman in this second-hand, dehumanised manner that allows him to subject his star to this half-life. In his unconscious state, Truman is unmoving, unaware, and vulnerable. Both Truman and the apple are ordinary subjects that have been unwittingly elevated to iconic status in an artist’s creative project. To Christof, the ‘True Man’ is an object for consumption. The showrunner packages Truman’s authenticity as entertainment for the masses, denying Truman’s autonomy in favor of satisfying the voyeuristic craving for “reality” in storytelling.

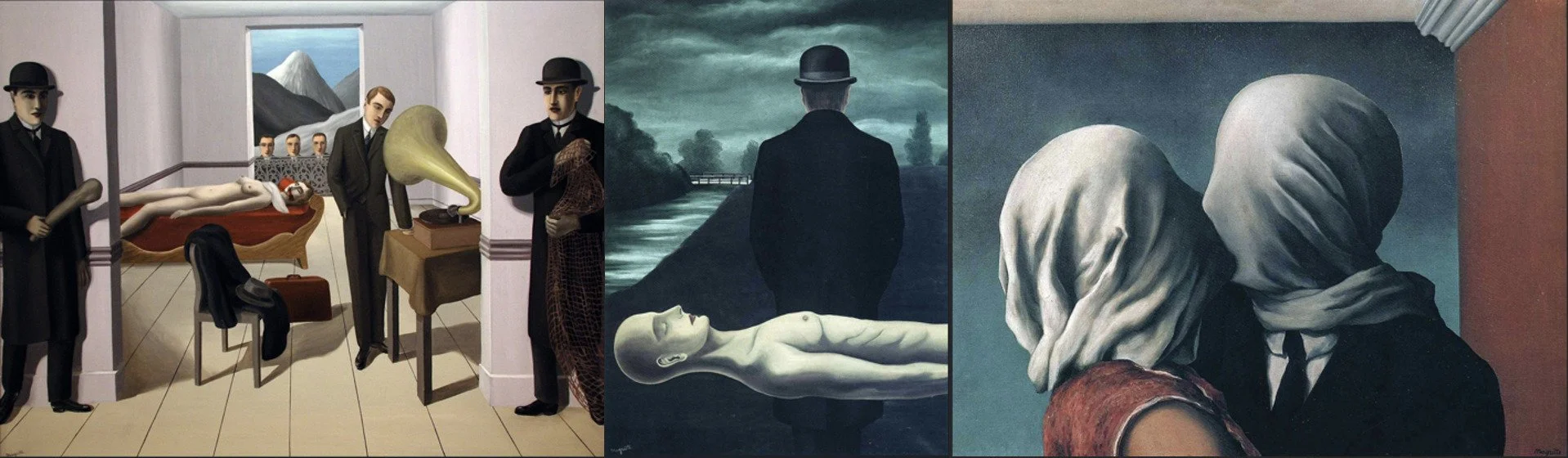

(left) René Magritte, The Menaced Assassin, 1927, Oil on canvas, 150.4 x 195.2 cm.

(middle) René Magritte, The Musings of the Solitary Walker, 1926, Oil on canvas, 139 x 105 cm.

(right) René Magritte, The Lovers, 1928, Oil on canvas, 54 x 73.4 cm.

Images courtesy of WikiArt.

The concept of The Truman Show, as it exists within its fictional reality, is undoubtedly morally abhorrent. Broadcasting the entirety of a man’s life without his consent is hardly defensible, but perhaps the most twisted “plotline” within the show is the apparent passing of Truman’s father. Christof orchestrates a sailing accident in which Truman’s father is thrown from their boat and carried away by the stormy waters. Truman is wracked with survivor’s guilt, blaming himself for his father’s death and developing a crippling fear of water. The latter is, of course, the showrunners’ intended effect, designed to keep Truman trapped on the set. Where Truman’s loss was fabricated, Rene Magritte’s was devastatingly real. When he was thirteen, his mother drowned herself, her body reportedly recovered nude, with her dress covering her face, a detail often linked - despite Magritte’s resistance to biographical readings - to works such as The Menaced Assassin (1927), The Musings of the Solitary Walker (1926), and The Lovers (1928). Across these paintings, shrouded bodies, surveillance, and obstructed intimacy suggest a lingering trauma that Magritte would likely have denied.

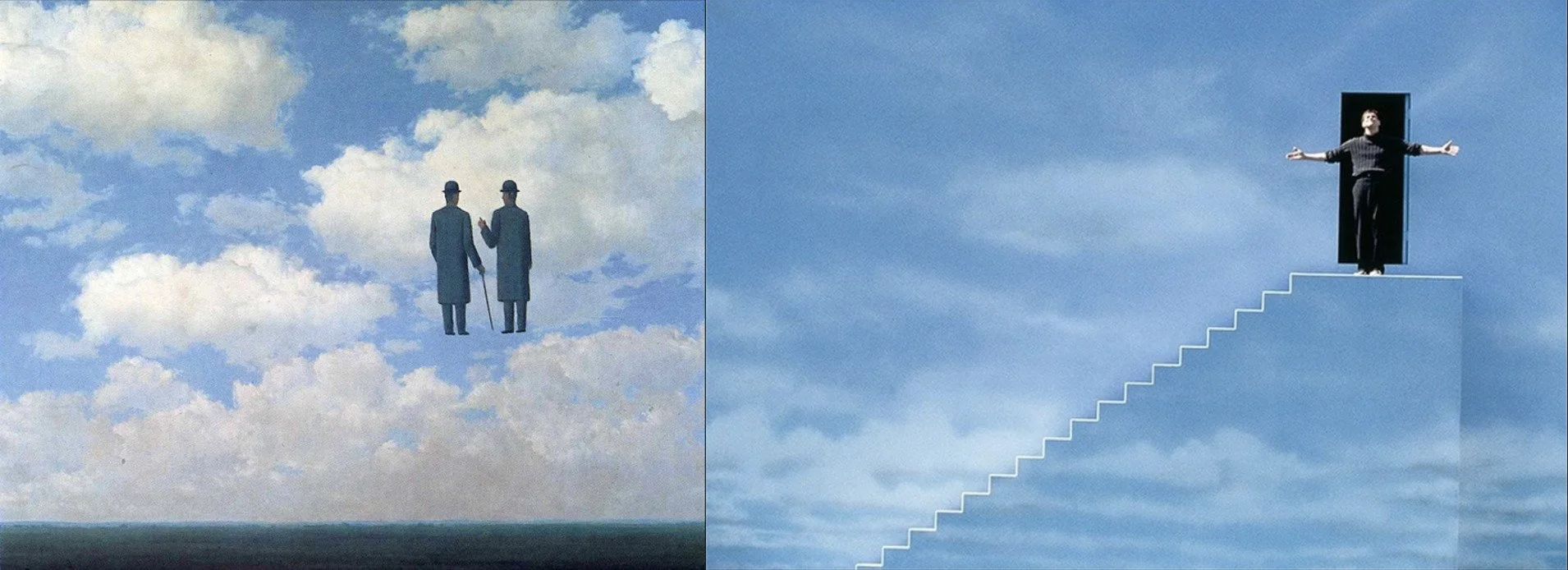

(left) René Magritte, The Infinite Recognition, 1963, Oil on canvas.

Image courtesy of WikiArt.

(right) Still from Peter Weir, The Truman Show, 1998.

Image courtesy of IMDB.

With each on-set mistake, Truman grows closer to the revelation that he is trapped within a surreal nightmare. Over the decades, the show’s production has become reliant on Truman’s strict adherence to routine. It is Truman’s suburban conformity that keeps him imprisoned. Magritte also incorporates the theme of conformity into his paintings, with his many anonymous bowler-hat-wearing bourgeois men. They appear in many paintings and are even replicated multiple times within the same painting, as in Golconda (1953). Whenever Truman deviates from his routine, his attempts to escape are carefully obstructed, reinforcing the impossibility of leaving his constructed reality. Truman is finally confronted with the magnitude of his confinement when his boat, the aptly named Santa Maria, runs into the sky dome. This artificial sky, functioning as an illusion of freedom, parallels Magritte’s recurring use of the sky in works such as The Seducer (1953), The Victory (1939), and The Human Condition (1935) where reality is similarly revealed as a fragile and staged construct. Perhaps the most famous shot from The Truman Show is Truman standing before the chasm of the exit door, bowing to his audience. The cruel irony of disguising the dome that marks the boundary to his world with the freedom of the sky is finally being corrected. The composition of the shot, as well as the sense of hope and infinite potential, is nearly identical to that of The Infinite Recognition (1963).

Both The Truman Show and Magritte’s surrealist oeuvre serve as investigations into the construction of reality. They seek to find where the boundary between authenticity and illusion lies, especially in our contemporary moment, when the social media panopticon has brought Christof’s surveillance apparatus closer to non-fiction. There is a constant form of curation and performance that has become automatic in online interaction, where authenticity and truth are replaced by the sensational. Both the painter and the filmmaker warn against unthinking conformity and blind acceptance in what we see and are told. Together, their works beg us to question if we are accepting the thin veil that masks reality for the thing itself.

Bibliography

Freer, Scott. “Magritte: The Uncanny Sublime.” Literature and Theology 27, no. 3 (November 21, 2012): 330–44. https://doi.org/10.1093/litthe/frs056.

Jackson, Tony. “Televisual Realism: ‘the Truman Show.’” Mosaic: An Interdisciplinary Critical Journal 43, no. 3 (September 2010): 135–50. https://www.jstor.org/stable/44029487.

Lavoie, Dusty. “Escaping the Panopticon: Utopia, Hegemony, and Performance in Peter Weir’s the Truman Show.” Utopian Studies 22, no. 1 (2011): 52–73. https://doi.org/10.1353/utp.2011.0033.

MOMA. “The False Mirror.” The Museum of Modern Art. MoMA, 2013. https://www.moma.org/collection/works/78938.