Tracy Emin’s A Second Life at Tate Modern

By Sadie McGraw

Tracy Emin, I Never Asked to Fall in Love, 2018, Oil on canvas, 40 x 50 cm. Image courtesy of Tracey Emin.

For nearly forty years, Dame Tracey Emin’s raw, confessional work has been at the forefront of the postmodernist and Young British Artists movements. Working throughout nearly every art medium, Emin will have her largest exhibition at the Tate Modern in London next week, including her essentials as well as never before shown pieces. With more than 90 works, Emin describes A Second Life as a “true celebration of living” and It is only fitting for this London native’s most comprehensive collection is to be exhibited in the Tate Modern.

A viciously present theme throughout A Second Life is, ironically, death. In 2020, Emin was diagnosed with squamous cell cancer that nearly took her life. This brush with death inspired the title of the exhibition, as she feels she now has a chance at a “second life” to solidify both who she is and what she lives for. Her relationship with cancer, disability, and infraction are addressed in pieces like Ascension (2024) as Emin grapples with a new relationship with her body after surgery. Amongst this, Emin’s other lifelong themes in A Second Life are personal trauma, love, and autobiography.

My Bed (1998):

Tracy Emin, My Bed, 1999, Mixed media. Image courtesy of Tate Modern (London).

As arguably Emin’s most prominent pieces, My Bed returns to the Tate, where it was first exhibited in 1999. The year prior, in 1998, Emin spent four straight days in bed, without eating or drinking anything but alcohol. The result was My Bed, consisting of her disheveled bed dressed in soiled sheets, with her bedroom objects scattered around the bed.

Looking at the sculpture, the bed feels like it could belong to anyone, but the work feels excruciatingly personal and invasive. My Bed displays addiction and breakdown, yet its creation defies its inspiration. The fact that My Bed exists at all means that Emin was able to overcome her breakdown, exemplifying a central theme throughout A Second Life: Emin’s refuge through art.

It’s familiar. It’s sexy. It’s relatable. Emin’s ability to create emotionally charged and accessible pieces speaks to her mastery of her subject and medium, a key component in what makes this exhibition stunningly moving.

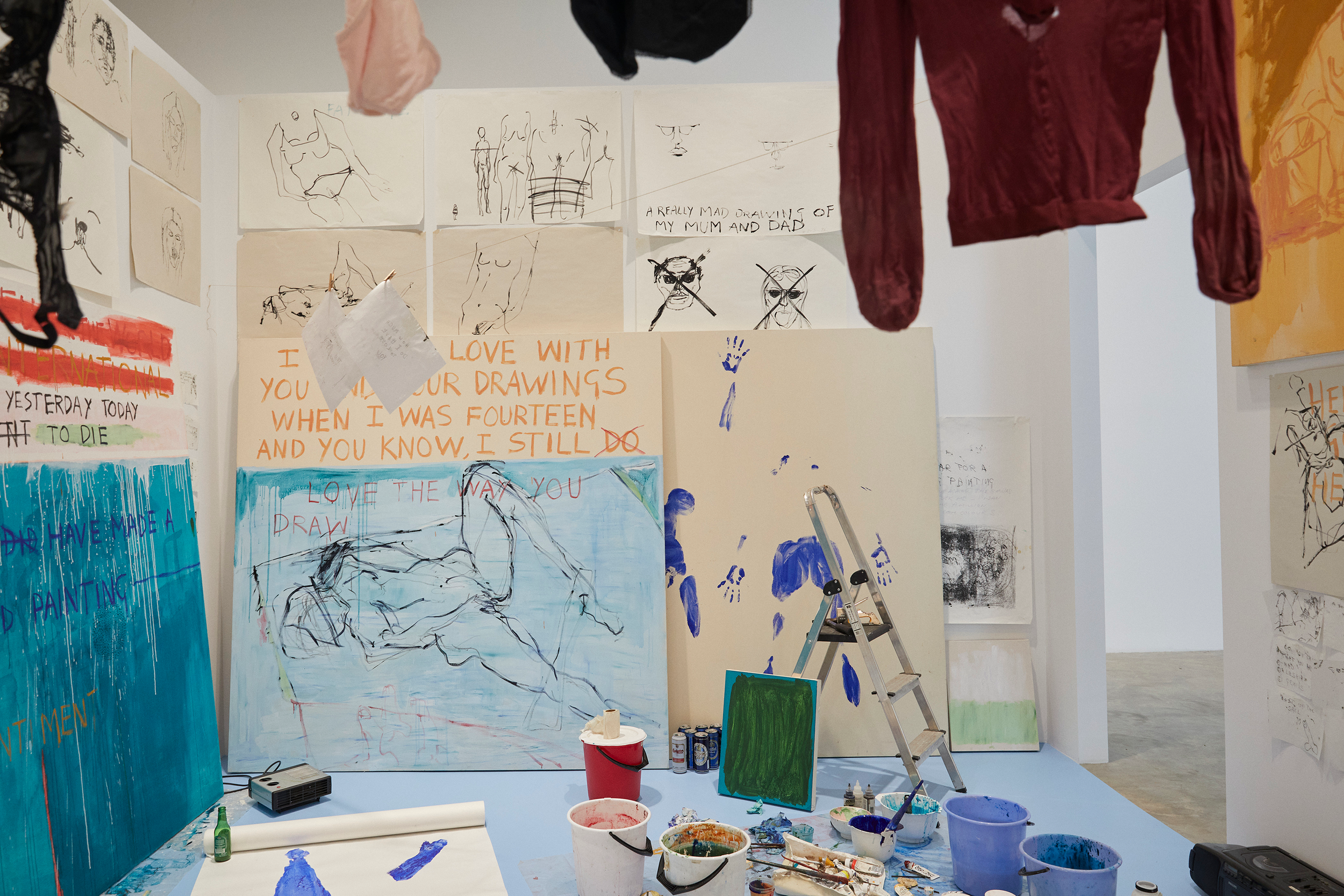

Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made (1996):

Tracy Emin, Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made, 1996, Installation. Image courtesy of Xavier Hufkens.

Along with My Bed, Exorcism of the Last Painting I Ever Made is at the center of Emin’s new exhibition. In 1996, she locked herself in a Stockholm gallery room for three weeks. Being entirely naked, Emin grapples with her guilt and anxiety around painting, as she had abandoned painting in 1990. The result is an installation piece featuring the actual room where Emin produced 12 large paintings and 79 works on paper. What stands out about Exorcism is not just its slightly absurd mode of creation, but Emin’s position as both the model and artist within the work. Emin works to challenge universal perceptions of viewership and the act of viewing, while also tackling her own emotions around painting. She says, “I felt at the time that, in doing the Exorcism, I was regaining my faith in painting and in art.”

Why I Never Became a Dancer (1995):

Tracy Emin, Why I Never Became a Dancer. 1995, video. Image courtesy of Tate Modern.

As a testament to her mobility between mediums, Emin explores themes of sex, trauma and liberation in this film. The video begins with a voiceover by Emin, telling a story about her adolescence over grainy camera footage of her hometown, Margate, possessing an indescribable but present feeling of unease. She tells us that she entered a disco championship at 15 to use dancing as a liberation from all she had experienced. Emin builds up an idea of winning this dance competition as her escape from Margate and from all that had happened to her. But just as she’s about to win, the men she had slept with started chanting “slag” at her repeatedly until she ran out of the room, and in turn “out of Margate”. The film ends with a compilation with Emin dancing, a celebration in retrospect of her reclamation of joy from these men.

This work is pivotal in Emin’s oeuvre and thus, pivotal in A Second Life. She grapples with trauma through her work, where many expressions of it are dark, but Why I Never Became a Dancer is a representation of Emin’s deliverance from this trauma and an acceptance of her past. The film is a source of both acceptance and release in the exhibit.

“There’s the canvas, there’s me, and there’s this other space between us, and you have to go through it, that space, and you drag in everything behind you with you into it. It’s like going through a weird tunnel. And the painting is whatever you’ve dragged through the tunnel with you,” says Emin, describing what it feels like to be back in the studio after her bout with cancer, but it is widely applicable to all of her pivotal and emotional work. For Emin, everything is revolving around her art now. With now having a chance at “a second life”, she feels that art and creation at the center of her world these days, stating, “Everything, now, is about the art.” A Second Life is a fervent expression of Emin’s resilience and a must-see this spring.

Bibliography:

“Tracy Emin: A Second Life,” Tate Britain, 8 September 2025, https://www.tate.org.uk/press/press-releases/tracey-emin-a-second-life

Louisa Buck, “Tracey Emin: ‘I’ve done more in my last five years than in the whole rest of my life’,” The Art Newspaper, 13 February 2026, https://www.theartnewspaper.com/2026/02/13/tracey-emin-artist-interview-i-have-done-more-in-my-last-five-years-than-in-the-whole-rest-of-my-life

Charlotte Higgins, “Tracey Emin on reputation, radical honesty – and Reform,” The Guardian, 14 February 2026, https://www.theguardian.com/artanddesign/2026/feb/14/tracey-emin-interview-tate-modern-regrets-smoking