The Traitors: A Scottish 'vanitas'

By Anna Barlow

It is safe to say that the UK has been thoroughly gripped by The Traitors. Week after week, viewers submit themselves willingly to an hour of frustration and suspense, watching the age-old game of deception, trickery, and masterful bluffing as the traitors continue to get away with murder. The experience is almost unbearable, yet utterly irresistible.

BBC, The Traitors UK, Series 4: Episode 3, 2026. Image courtesy of Euan Cherry.

Perhaps part of its appeal lies in the moral freedom it offers, as most of us do not often get to lie and deceive without burdening our consciences. The Traitors provides us with a rare release: a space in which viewers can indulge in manipulation and devious ploy with no costly ethical repercussions. Instead, we cheer on figures we would condemn elsewhere and revel in their cash prize.

Yet beyond the psychological gameplay, another force is quietly at work. Acting almost as covertly as the traitors themselves, the visual language of the programme shapes it as sphere of uncertainty and dread. Scottish artworks, architecture, and religious symbols are the backbone of the show, transforming The Traitors into something resembling a living Dutch still-life, entrenched in morality, illusion and national identity.

The game unfolds within Ardross Castle in the Scottish Highlands, a looming Scotch Baronial-style structure whose turrets for secret scheming, spiral stone staircases with crow-stepped gables and conical roofs seem purpose-built for menace. This is not merely the picturesque location it claims to be: it is a stage for betrayal.

Ardross’s Scottish architecture in the opening façade of the show is the first poignant emblem of The Traitors’ sinister nature. Initially designed to project authority of the landed elite with an impenetrable stronghold, the castle possesses ‘a cloud capp’d theatrically rooted in illusion’ and is ‘unmistakably Scottish’. Baronial style is itself a Romantic revival of the Gothic aesthetic, what Alvin Jackson described as a distinctly ‘Caledonian reading’. In The Traitors, the fortress revisits this history but becomes something ever more insidious, as a veil of ignorance for murder. Within its walls, loyalty is tested, the truth is obscured and faith is constantly in jeopardy.

Its architectural eclecticism draws on features of the French château, Flemish gable, and Italian palazzo, not to mention all those Anglo-Norman assimilations, reflecting Scotland’s long-standing engagement in Europe. As ‘Scotland was never a country over-endowed with rich agricultural land, but it is blessed with a rugged coastline and good deep-water harbours…this by necessity, cultivated an interest in trade and travel’.

The result of panning to this architecture is a demonstration of identity that is European in influence, yet undoubtedly Scottish in character: a nationhood the show exploits to full effect.

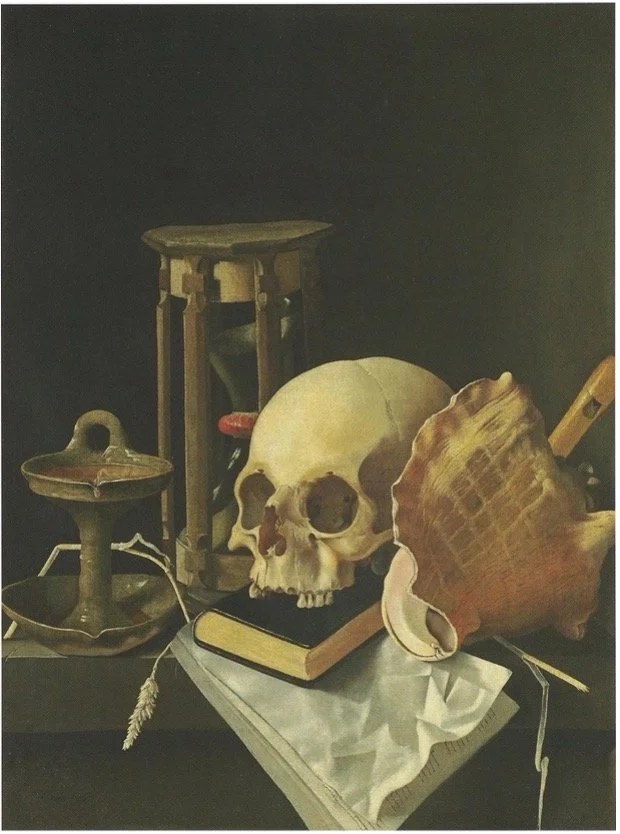

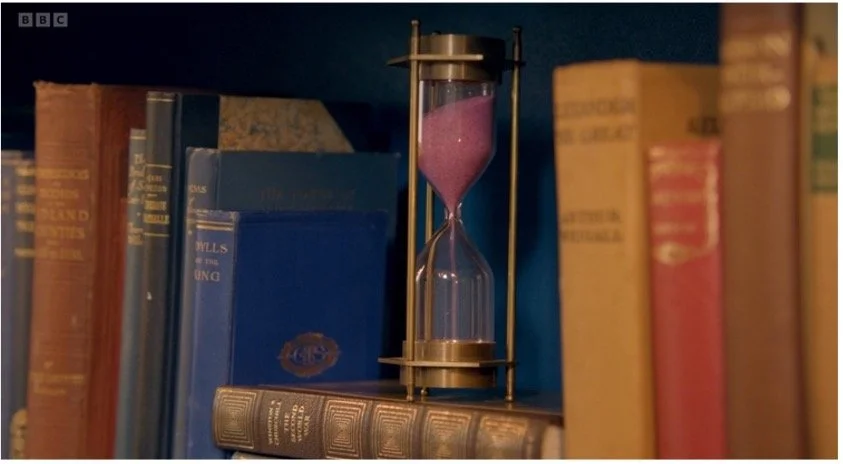

These coupled themes of Scotland and malevolence continue in the interior. The interview rooms are laden with objects and artworks that serve as sinister tokens: notably in most scenes, the camera pans to skulls, sand timers and shells all building a feeling of impending dead and the later, resurrection. The same are seen in the work of Adriaen Coorte.

Adriaen Coorte, Vanitas Still Life with skull and hourglass, 1868. Oil on canvas, 50.1cm x 41.4 cm. Image courtesy of Sothebys.

BBC, The Traitors UK, Series 4: Episode 7, 2026. Image courtesy of BBC iPlayer.

BBC, The Traitors UK, Series 4: Episode 7, 2026. Image courtesy of BBC iPlayer.

These curiosities recall the vanitas paintings of the Dutch Golden Age, where artists employed Calvinist symbols of decay and time to remind viewers of life’s transience. The message on the set of The Traitors is clear: the earthly pleasures and comfort the players seek in the castle are fleeting; death, for most, is inevitable. Only those who correctly seek the truth are rewarded with riches and survival in the game, like those of the Calvinist period who seek the truth in God, according to scripture, are rewarded with eschatological wealth and immortality.

This imagery strongly resonates with Scotland’s own Calvinist past. Rooted in anti-materialism and moral reckoning, the Calvinism from John Knox rejects hedonistic excess and emphasises the principle of ‘memento mori’, meaning ‘remember you must die’. One cannot bring riches and sin into the kingdom of heaven, as one can recall from Matthew 19:24, ‘it is easier for a camel to go through the eye of a needle than for someone who is rich to enter the kingdom of God’. In The Traitors, these same symbols quietly foretell the players’ fate. Although the game revolves around a cash prize, the set insists of the futility of riches in the face of elimination.

The peculiarities, paintings and poignant sculptures in Gothically lit rooms insist on the looming destiny of the players and entrench them in a theatrical vision of the Scottish past. The Traitors provides an imitation of the long-established aristocratic desire to travel and collect for its participants, allowing them and us, the viewer, unfettered access to an era when ‘eclecticism was inevitable… often extravagant to the point of absurdity.’ Set design purposefully transforms the visible spaces into indulgent imitations of the vanitas assemblages of historic Scottish collectors.

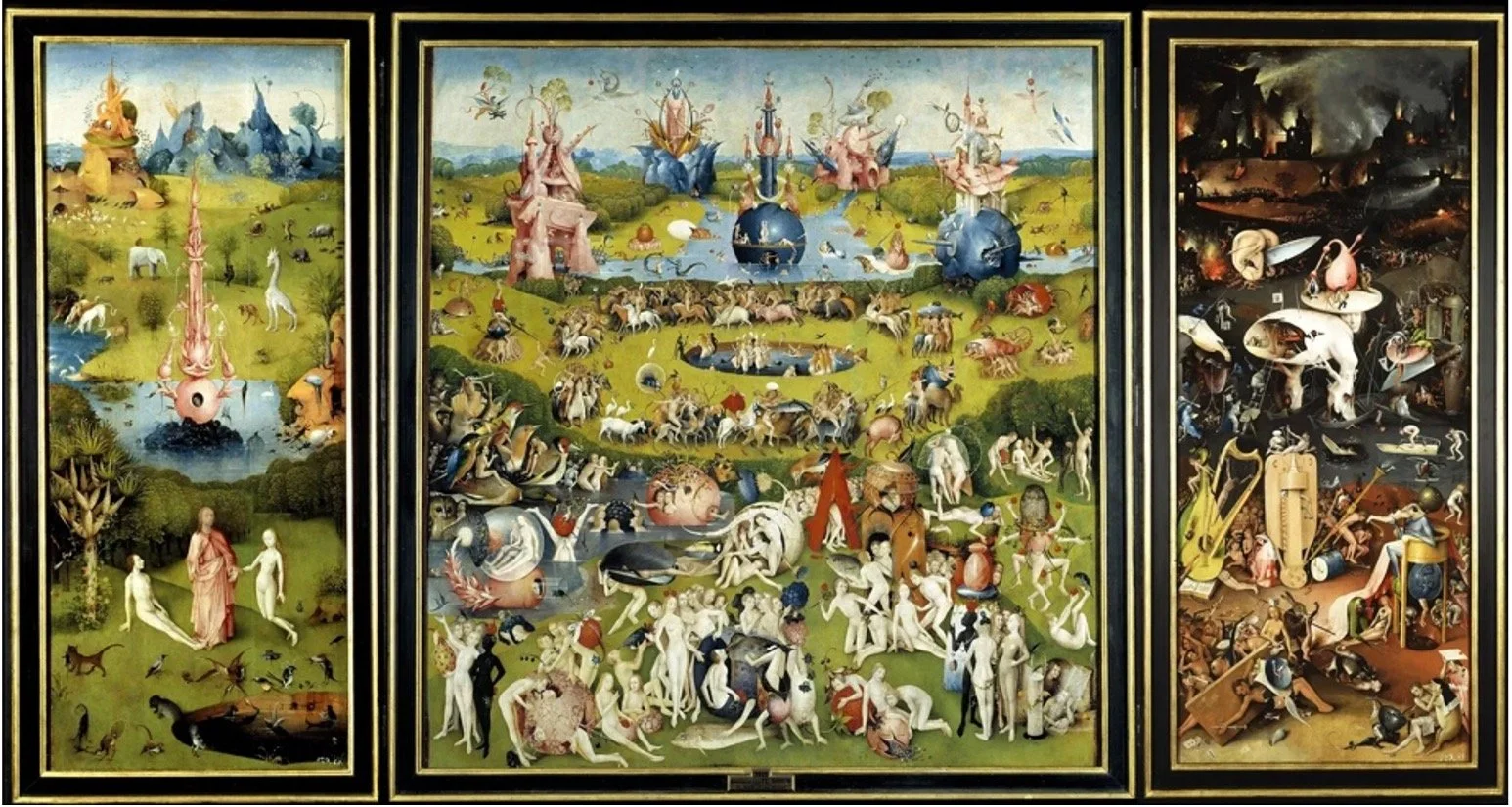

Even the breakfast table, where players gather each morning to discover who has been ‘murdered’, resembles a considered still life collation. Fruit, foliage, and feathers recall traditional conventions that historically symbolise temptation and an illusion, visually alluding to how the pleasures and comforts in the castle are employed to veil the traitors' masterful ploy. The tokens selected in their soft pastels embody the quality of deceptive beauty in the postlapsarian garden of ‘pleasures’ within Hieronymus Bosch’s triptych The Garden of Earthly Delights (1490-1500). As Paul describes, like the faithfuls, mere morals cannot see the full truth of reality, only through a ‘dark glass’ (1 Corinthians 13:12).

Hieronymus Bosch, The Garden of Earthly Delights, 1490-1500. Oil on oak panel, 205.5 x 384.9 cm, Museo del Prado Madrid. Image courtesy of Museo del Prado Madrid.

BBC, The Traitors UK, Series 4: Episode 7, 2026, Image courtesy of BBC iPlayer.

The symbolism extends outdoors. In one challenge of Series 4, Episode 7, the camera captures the castle’s ornamental fountain depicting The Boar Hunt. Crafted from Pelham stone and designed by the Bromsgrove Guild of Applied Art, it is a typical dramatic scene of the dangerous pursuit of a wild boar, symbolising courage, masculinity, and aristocratic sport. We are never far from the Scottish concept of the Braveheart. Yet, in this particular challenge, the fountain spills red ‘blood’, transforming an emblem of bravery into a chilling reminder of murdered faithfuls. Valour is drowned by betrayal.

BBC, The Traitors UK, Series 4: Episode 7. Image courtesy of BBC iPlayer.

Inside the dining room too a painting of an owl appears as the players feast, while one poor soul unknowingly takes their final meal. The owl, typically used as a symbol of wisdom, detached material desires, and the capacity to see through darkness and ignorance, visually mirrors the position of the most perceptive faithfuls. However, ironically, these are the players who most often fall victim to the traitors.

This game we love and and continuously watch is a timeless classic. It is a story retold for millennia, and the set design allows us a little melodramatic indulgence: the faithful are the loyal apostles, the traitors infamously deceive as Judas the betrayer once did, and we, the viewers and our beloved Claudia Winkleman are the omniscient Christ that oversee the players every move with quasi-divine knowledge.

The set of this iconic tale cleverly orchestrates it as one also of Scottish identity, through the camera’s careful capturing of art. It plays on the country’s historic architecture, eclecticism and Calvinist ideas of death that echo Dutch vanitas to ultimately enhance this game of secrecy, betrayal, and traitorous ploy: a twenty-first century last supper.

Bibliography

Ardross Castle - Luxury venue in the Scottish Highlands. “Heritage - Ardross Castle,” January 24, 2023. https://ardrosscastle.co.uk/heritage/.

BBC iPlayer. “The Traitors - Series 4: Episode 7,” 2026. https://www.bbc.co.uk/iplayer/episode/m002pwrc/the-traitors-series-4-episode-7?seriesId=p0db9b2t-structural-4-m002nzpr.

Black, David J. “Miles Glendinning and Aonghus Mackechnie, Scotch Baronial: Architecture and National Identity in Scotland.” The Innes Review 70, no. 2 (November 1, 2019): 221–24. https://doi.org/10.3366/inr.2019.0233.

Museo del Prado. “The Garden of Earthly Delights Triptych.” Museodelprado.es. Museo del Prado, 2016. https://www.museodelprado.es/en/the-collection/art-work/the-garden-of-earthly-delights-triptych/02388242-6d6a-4e9e-a992-e1311eab3609.

Rakewell. “The Traitors Milks Art History.” Apollo Magazine, January 5, 2026. https://apollo-magazine.com/traitors-bbc-claudia-winkleman-painting-challenge-fiona/.

The Bible. Macon, Ga.: Smyth & Helwys, 1994.