Gabriele Münter (1877-1962)

By Audrey O’Rafferty

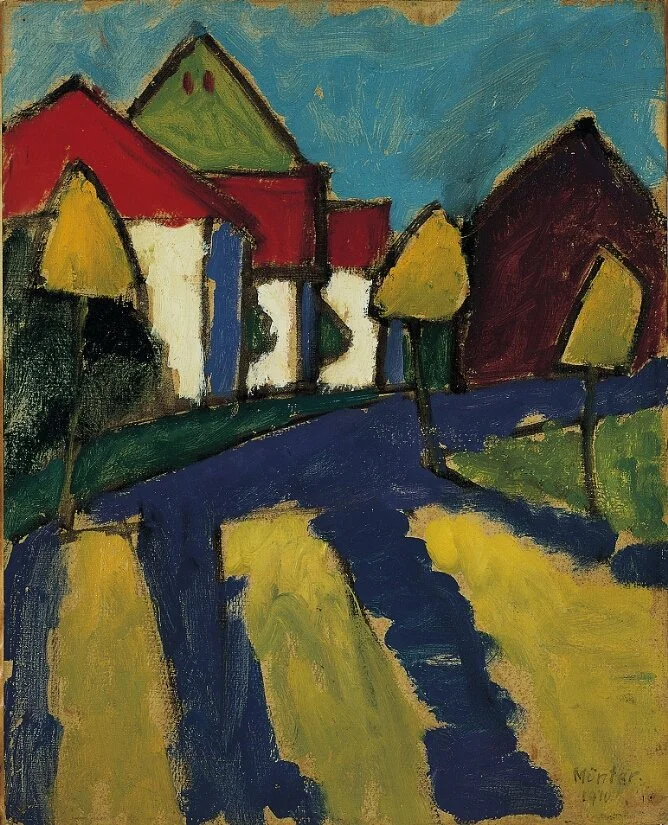

Gabriele Münter, Lower Main Street, Murnau, 1910, oil on textured cardboard, 41.3 x 34.0 cm, Norton Simon Museum, Gift of Mr. David Gensburg.

Image courtesy of Gabriele Münter / Artist Rights Society.

During a school fieldtrip to the Norton Simon Museum a childhood friend said to me: ‘That looks like something I did when I was five years old.’ Such a phrase is often heard in regard to modern and abstract art, and it has come to deeply irritate me. The painting in question was Gabriele Münter’s Lower Main Street, Murnau (1910). Perhaps it does seem like a child could have painted it, though investigating the historical and artistic context of Münter’s work reveals its deeper significance within her time and the Expressionist movement.

Münter was born 19 February 1877 and emerged into a world which heavily excluded women and discouraged them to become an artist. Although her gender barred her from gaining an education at any mainstream art institution, Münter was accepted in the progressive Phalanx School in Munich. Here, she was pressured into a tumultuous relationship with the abstract painter Wassily Kandinsky, who was married at the time. Even though Kandinsky championed her work and talent, he nevertheless categorised her paintings as ‘feminine’, thus diminishing them. Such sexism extended into the Expressionist group Der Blaue Reiter, of which Münter was a founding member. Leading members of the group, like Franz Marc, explicitly associated women with nature and the ‘primitive’, whereas men were associated with intellectualism. Importantly, sexism framed the conditions under which Münter’s work has been received, both then and now.

Flattened picture planes, brushwork which evidenced the artist’s hand, and simplified forms are all consistent with Der Blaue Reiter and German Expressionism’s rejection of academic tradition in favour of simplicity. Moreover, the simplified composition of Münter’s Lower Main Street, Murnau (pictured above) is reflective of Münter’s desire to depict the ‘essential nature’ of her experiences. Art historical scholarship has traditionally regarded her work as lacking ‘sophistication, intelligence, and innovation’. These notions play into the sexist stereotype of woman artists not having substantive dedication to their art practice, viewing Münter’s work as being ‘calculated to appear childlike’. Such background knowledge not only denies the validity of Münter’s style but also speaks to how such off-handed denials of artistic merit, like ‘a five-year-old could have done this’, can play into sexist tropes, even if unintentionally.

So, perhaps a five-year-old could recreate the line, form, and colour of Lower Main Street, Murnau, but a deeper consideration of Münter’s artistic approach and context reveals that that is not really the point.

Aside from this, Münter had all of her works, alongside some from Der Blaue Reiter, transported to her house in the 1930s to protect them from Nazi confiscation; the artworks were never found despite multiple searches. Münter lived most of her life in Murnau, with a brief stint in Switzerland, and passed away at home in May 1962.

Bibliography

“Gabriele Münter: The Great Expressionist Painter.” Apollo Magazine, November 8, 2024. https://apollo-magazine.com/gabriele-munter-great-expressionist-thyssen-bornemisza/.

“Gabriele Münter.” National Museum of Women in the Arts. https://nmwa.org/art/artists/gabriele-munter/.

Klassmeyer, Katy. “On Their Own: Reconsidering Marianne Werefkin and Gabriele Münter.” In Women in German Expressionism: Gender, Sexuality, Activism, edited by Anke Finger and Julie Shoults, University of Michigan Press, 2023.